When many designers think of skills, they list tools (Figma, Sketch, Adobe) or outputs (wireframes, prototypes, presentations). Those matter and they’re evidence of work, but they’re not the skills itself. Real transferrable skills are about how you think and approach your work. They’re the capabilities underneath the deliverables, that translate across roles, industries, and contexts.

Here's the challenge: you've been doing this work for years, but you probably haven’t tried to articulate it clearly. And if you can't name it, you can't sell it.

The Translation Gap

I've coached dozens of designers and researchers through career transitions. The pattern is always the same. They know they're good at what they do. They have the portfolio to prove it. But when I ask them to describe their skills without referencing specific tools or deliverables, they struggle.

"I run user research sessions." "I create wireframes and prototypes."

These aren't skills. These are activities. They describe what you make, not what you're capable of.

The designers who navigate transitions successfully? They've learned to translate. They can describe the same work in terms of capabilities that travel.

Let me show you what I mean.

Stakeholder Management: The Skill You Don't Call a Skill

You know how to run workshops. You've facilitated dozens of them: design critiques, brainstorming sessions, alignment meetings with cross-functional teams.

You probably don't think of this as "stakeholder management." But that's exactly what it is.

When you run a workshop, you:

- Ask questions to surface needs and constraints

- Navigate conflicting priorities between different groups

- Build consensus around a direction

- Manage group dynamics so the loudest voice doesn't win

- Follow up to maintain momentum

This same skill applies to:

- Managing client relationships

- Navigating organizational politics

- Building executive buy-in for initiatives

- Leading cross-functional teams

- Networking and building professional relationships

It's the same capability. Different context.

The designer who says "I facilitate workshops" is describing an activity. The designer who says "I build alignment across stakeholders with competing priorities" is describing a skill that works in product management, strategy, operations, leadership… anywhere decisions involve multiple perspectives.

That's what transfers.

Systems Thinking: You Do This Every Day

If you've ever mapped a user journey, you're a systems thinker. If you've designed a service blueprint, identified pain points across touchpoints, or connected user needs to business requirements, you already think in systems.

Most designers don't recognize this as a distinct skill because it's so embedded in how they work, but systems thinking is one of the most valuable capabilities you can have, and it's rare outside of design.

What systems thinking looks like in design:

- Mapping how different parts of an experience connect

- Identifying downstream effects of design decisions

- Finding leverage points where small changes create big impact

- Understanding how user, business, and technical constraints interact

What systems thinking looks like elsewhere:

- Organizational design and team structure

- Business model innovation

- Operations and process improvement

- Strategic planning

- Market analysis

When I transitioned from design into operations, I wasn't learning new skills. I was applying the same systems thinking I'd developed mapping user journeys to team workflows instead of customer experiences.

The capability was already there. I just needed to reframe how I talked about it.

Research and Synthesis: The Meta-Skill

You know how to enter an unfamiliar problem space, ask the right questions, and distill insights that drive decisions. You've done this for user research. You can do this for anything.

Research and synthesis isn't about knowing how to conduct interviews or run usability tests. It's about structuring ambiguity and then using data to solve a problem.

In design, this looks like:

- Understanding user needs through observation and conversation

- Identifying patterns across disparate data points

- Translating insights into actionable recommendations

- Building a shared understanding across teams

Outside design, this applies to:

- Market research and competitive analysis

- Strategic planning and opportunity identification

- Due diligence for investments or partnerships

- Entering new industries or domains

- Organizational diagnostics

When someone asks "how would you approach this unfamiliar problem?" you already have a process. You do discovery. You ask questions. You synthesize what you learn. You identify what matters most.

That's a meta-skill. It works everywhere.

The Pattern: How vs. What

Notice the pattern in all of these examples? The transferable skill is never the deliverable. It's the thinking that produces the deliverable.

What you make: Wireframes, prototypes, journey maps, research reports How you think: Systems thinking, synthesis, facilitation, strategic framing.

What you make is context-dependent. How you think travels with you. This is why designers who focus on tools struggle during transitions. Figma proficiency doesn't transfer. The ability to translate complex requirements into testable solutions does. This is also why the best design portfolios don't just show finished work, they show process. They demonstrate how you think, not just what you produced.

Why This Matters Now

Design is consolidating. Job descriptions now ask for "Product Designers" who can do UX, UI, research, and strategy. "Specialist" roles are disappearing. The market is rewarding designers who can articulate how their skills connect across the full product lifecycle.

If you've been deep in one area like research, visual design, strategy you don't need to become something else. But you do need to show how what you do connects to adjacent disciplines. The designers navigating this shift successfully aren't the ones learning entirely new skillsets. They're the ones recognizing what they already know and translating it for new contexts.

Exercise: Map Your Capabilities

Here's what I have designers do when we work together:

Step 1: List 5-10 things you do regularly in your current role Be specific. "Run user interviews." "Create high-fidelity prototypes." "Facilitate design critiques."

Step 2: For each one, ask "what am I actually doing beneath the surface?" Not the output. The capability that produces it.

- "Run user interviews" becomes "I structure conversations to uncover needs people can't articulate themselves."

- "Create high-fidelity prototypes" becomes "I translate abstract requirements into concrete, testable solutions."

- "Facilitate design critiques" becomes "I create environments where teams can give and receive difficult feedback productively."

Step 3: Ask "where else would this capability be valuable?" This is where you identify adjacent opportunities. The same skill applies in contexts you haven't considered yet. Most designers skip step 2. They go straight from activity to opportunity and wonder why nothing clicks. The translation happens in the middle, when you name the capability underneath the work.

What Comes Next

In my next post, I'll talk about change agility: how to read industry shifts before they're obvious, position yourself for adjacent opportunities, and reframe your narrative depending on context. Because here's the thing: identifying your transferable skills is half the equation. Knowing when and how to deploy them is the other half.

Together, they create a career that's both resilient and directional. You can adapt to market shifts without losing your through-line. You build expertise that compounds across roles instead of starting over every time.

That's how you survive shake-ups. That's how you build a career that lasts.

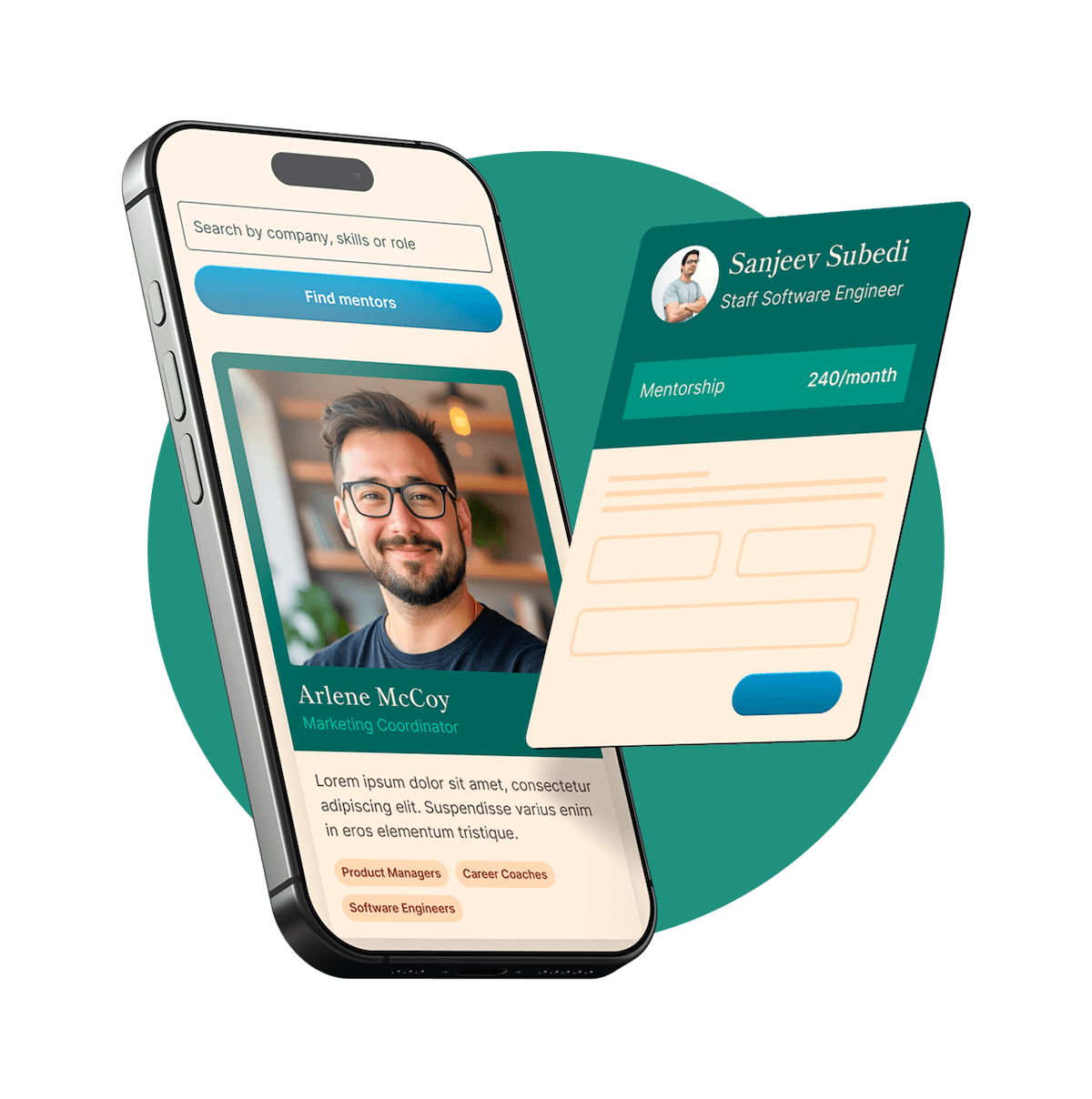

If you're trying to navigate a transition and need help identifying what actually transfers, let's talk. I work with designers one-on-one to map their capabilities, identify adjacent opportunities, and build the narrative that positions them strategically. Book a session on MentorCruise.

Read the previous post: Navigating Uncertainty