You may have seen the cycle play out before. A promising new candidate interviews well and excels on the job, only to crash and burn. Perhaps you've hired someone like this; or, like many of my past and present mentees, you might be someone like this.

Take one person, a brilliant software developer who beat out other candidates for a highly competitive job, but began struggling months after starting their new role.

Despite excitement about the problem space and team, they began getting distracted, started missing important details, and struggled to see projects through. Sometimes they were able to focus on something to the exclusion of all else. Their work was exceptional when they tapped into this elusive energy. But this also pulled them in the wrong direction, away from higher priority work to more exploratory tasks.

In 1:1s, they could feel their manager's unspoken frustration, almost as if she was asking herself: "What happened to the incredible person I hired?"

The developer couldn't find an explanation for their actions. They became increasingly depressed and self-recriminating, wracking their brain and wondering why they couldn’t just focus and get things done. Only with the ADHD diagnosis did things begin making sense.

By the time I began working with them as a career coach, they were pursuing an occupational assessment, but feared that the damage was already done. They doubted that accessibility accommodations would be enough to save their position or relationship with their manager.

Less than a year into their current role, they began job searching. Shortly after, they had multiple offers for other competitive positions. Despite struggling at work, they managed to impress various other prospective employers and secure multiple job offers. But would they go on to repeat this same cycle in one of the other roles now awaiting them? And how is it possible for someone to interview so well only to later struggle so much on the job?

The double-edged sword of ADHD

When faced with an exceptional interviewee who goes on to have performance problems, it's no wonder hiring managers are baffled. What happened to the all-star they thought they were onboarding? Some go so far as to wonder if they were duped by the interviewee’s charisma. How else could their instincts have led them so far astray?

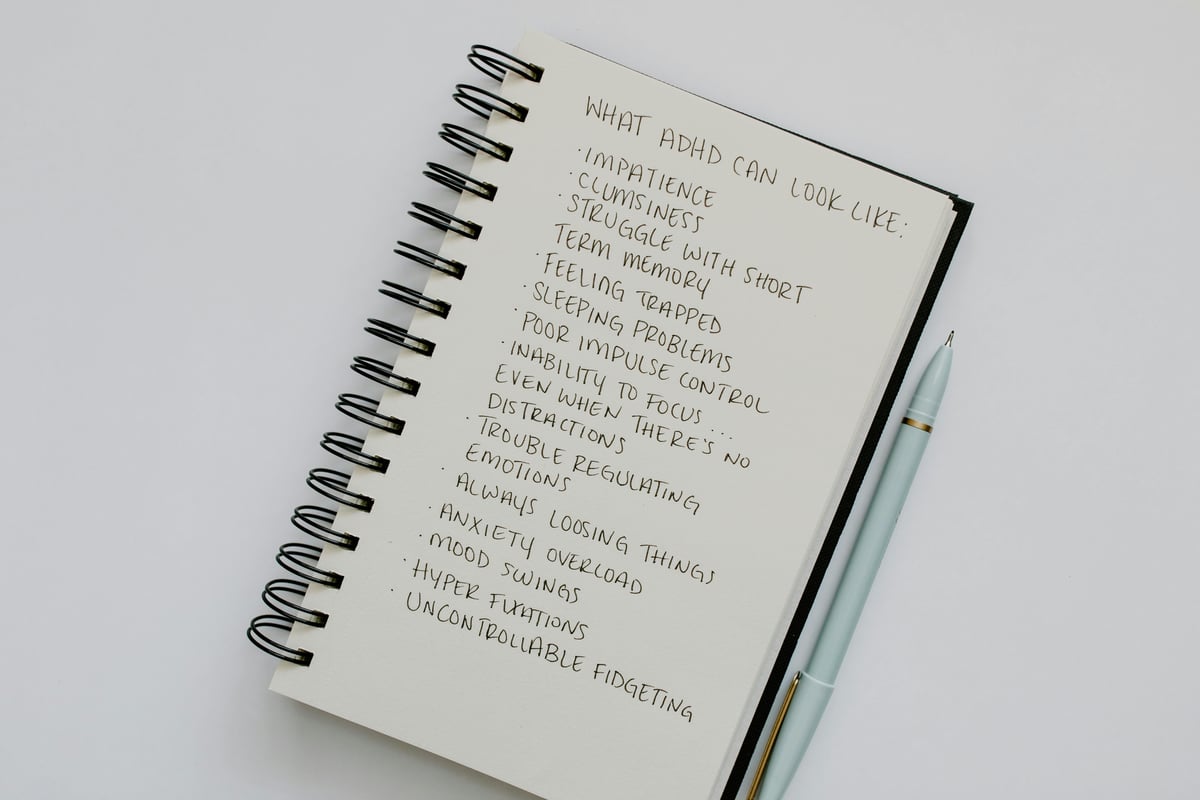

But what looks like deceit may actually be neurodivergence, a term for neurological variations such as ADHD, autism, AuDHD, dyslexia, dyspraxia, dyscalculia, and others.

Despite the word "neurodivergent" implying that a person has somehow deviated from an established norm, there is no one “normal” type of brain, and being "divergent" isn't inherently negative. Some divergences are favorable, others are unfavorable, and most are context-dependent.

Many neurotypical people are accustomed to thinking of ADHD as exclusively a cognitive impairment. They have trouble grasping how someone with executive dysfunction can ace an interview with flying colors and excel in the early days of their job. After all, “dysfunction” is right there in the name. But this line of thinking disregards the differing demands between a job interview and workplace.

A neurotypical person may be able to sustain the same level of performance in both an interview and in the workplace because their brains don’t respond, positively or negatively, to these distinct contexts. But these contextual differences may have a drastic impact on a neurodivergent brain. In fact, some ADHD people’s brains may be wired to do especially well in interviews. Under the right conditions, ADHD people have great capacity for excellence, resulting in this seeming paradox.

Why ADHD people excel in interviews

Research shows that many ADHD people have an incredible capacity to hyperfocus when working on areas of interest.

They make quick decisions, think outside the box, excel at brainstorming and often thrive in dynamic, high-energy environments, becoming great and convincing improvisers and delivering brilliant and well-timed responses without prior preparation. This makes people with ADHD both excellent presenters and thought leaders.

For some, deadlines and high-pressure situations are motivating and clarifying rather than stressful, allowing ADHD-havers to channel intense focus and clear thinking in a short but intense period of time.

From a young age, neurodivergent people also learn to hide behaviors that are poorly received, a practice known as “masking.” In interviews, individuals with ADHD may monitor themselves for behaviors like interrupting or fidgeting.

Masking is not intentional deception; it’s a survival tactic developed after years of criticism from peers and authority figures. Though this hypervigilance is exhausting, during an interview, an ADHD person can hide some of their symptoms for a few hours.

Given all this, it makes sense that ADHD people are dynamic, quick-witted, engaging, creative, intelligent, and adaptive in a timeboxed, high pressure job interview. And it’s no wonder that such an interviewee would get multiple job offers and beat out other candidates for the job. They make a great first impression.

From superstar to burnout

A job offer is extended, the interviewee gladly accepts, and then comes the daily grind.

If they’re extremely good at masking, the issues may not be immediately apparent. At first, a new employee may push hard to prove themselves, feeling the pressure to maintain the same level of excellence demonstrated in their interview or out of a desire to please, though they may not be consciously aware of this.

So the superstar interviewee becomes a superstar employee, at least for a while. Nobody knows that, beneath the surface, they’re working a hundred times harder than everyone else to keep it together. This puts them on a fast track to burnout.

When burnout comes and the mask begins to slip, managers may be frustrated, confused, and stymied as they see their employee struggling to complete the same types of tasks they once easily handled. Managers wonder what happened and even suspect their employee is intentionally beginning to shirk responsibilities or slack off. But this seeming indolence is actually a case of an unseen, unsustainable system finally falling apart.

Managers aren’t the only ones affected. ADHD people are often highly attuned to subtle emotional changes in others, too. If managers don’t communicate their frustrations or concerns openly, an employee may still sense that something is off without being able to pinpoint exactly what. This seeming discrepancy between what we sense and what we’re told can cause high levels of stress, uncertainty, and anxiety, which spirals into even worse performance.

This can be deeply psychologically damaging and demotivating for employees, leading to depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, and self-doubt. As a neurodivergent coach of neurodivergent people, I know firsthand the whiplash from making a great first impression to struggling in the day-to-day because I’ve both lived it and seen it. We, too, wonder where that confident, quick, clear headed person went. We, too, can feel the disconnect between who we were before versus now and wonder where our past self went.

Neurodivergence meets neurotypical expectations

As tempting as it is to blame oneself, neurodivergence isn't the problem. ADHD people can go to therapy, take medication, download special apps, make lists, take extensive notes, set alarms, and adopt all the systems, tools, and coping mechanisms in the world to mitigate their ADHD, and yet it still isn’t enough to meet the neurotypical world’s demands and expectations.

Take, for example, a student who processes information better while doodling in a notebook. They don’t look at their teacher while he’s talking, but they’re giving him the same amount of attention as their classmates.

Nonetheless, the teacher interprets this as inattention and disrespect, so the student is chastised for not paying attention and is forced to keep their eyes on the front of the classroom, which actually worsens their information retention. In this way, the neurotypical world’s interpretation of “acceptable” ways to pay attention punishes this student for doing the very thing that helps them succeed.

Now imagine how this looks in a big meeting room. Someone is giving an important presentation and one of your colleagues is doodling in their notebook, only glancing up occasionally to look at the slides. Is your conclusion that they aren’t paying attention?

If they’re tapping their fingers or jiggling a leg, are they being rude?

If they’re standing up in the meeting instead of sitting down, is it because they’re impatiently waiting for it to end?

Research supports that doodling, moving one’s body (stimming), and standing up are all ways to reduce cognitive load and improve attention, focus, information processing, and memory.

But, unfortunately, even when ADHD people are doing their best to pay attention and meet expectations, their behaviors are negatively interpreted through a lens of what’s considered “polite” or “acceptable”, rather than what’s best for their success. These behaviors are actually toolsets that neurodivergent people have developed over time, often subconsciously, to be successful.

Thus, neurodivergent people are constantly reckoning with social structures and expectations that are built around the needs and behaviors of neurotypical individuals. For their efforts, they may be reproached, rejected, criticized, given poor evaluations and lower grades, or even publicly humiliated (like a teacher calling out a student in front of the class). The world just won’t let them live. These “weird” behaviors just won’t do.

No wonder neurodivergent people try to hide the very behaviors that would help them cope in environments that are so mismatched from their cognitive needs.

Breaking the cycle

The onus to try functioning in a neurotypical world can’t continue falling on ADHD people alone. It’s not only exhausting, but it’s a waste of our unique talents and abilities. We’re smart, quick, creative, and great at divergent thinking. An ADHD person can be an incredible asset. Given adequate support, we have the potential to flourish and, let’s be honest, truly kick ass.

In the next article in this series, I’ll dive deeper into how to break the vicious cycle of superstar burnout and elaborate on how both managers and employees can work together to achieve better outcomes and create more ADHD-friendly workplaces.

Are you a neurodivergent person looking for mentorship or a manager seeking to support your neurodivergent employees? As a neurodivergent career mentor, I can help you create sustainable success for yourself and others. Let's connect!