We've all seen the stories of technology gone wrong. Job recruitment systems that are gender biased, facial recognition technology that doesn't work for BIPOC people, chatbots that spew vitriol or technology that otherwise fails on the social responsibility scale. As a startup founder, investor, business manager or technologist, you are being called upon to do better.

There are many high level ethical codes such as the Asilomar Principles or the Montreal Declaration which set out ethical principles that can serve as aspirational objectives. For example, the Asilomar Principles list safety, judicial transparency, responsibility, personal privacy, liberty and human values as part of the principles it seeks to uphold. Similarly, the Montreal Declaration speaks to values like well-being, respect for autonomy, sustainability, solidarity and democratic participation.

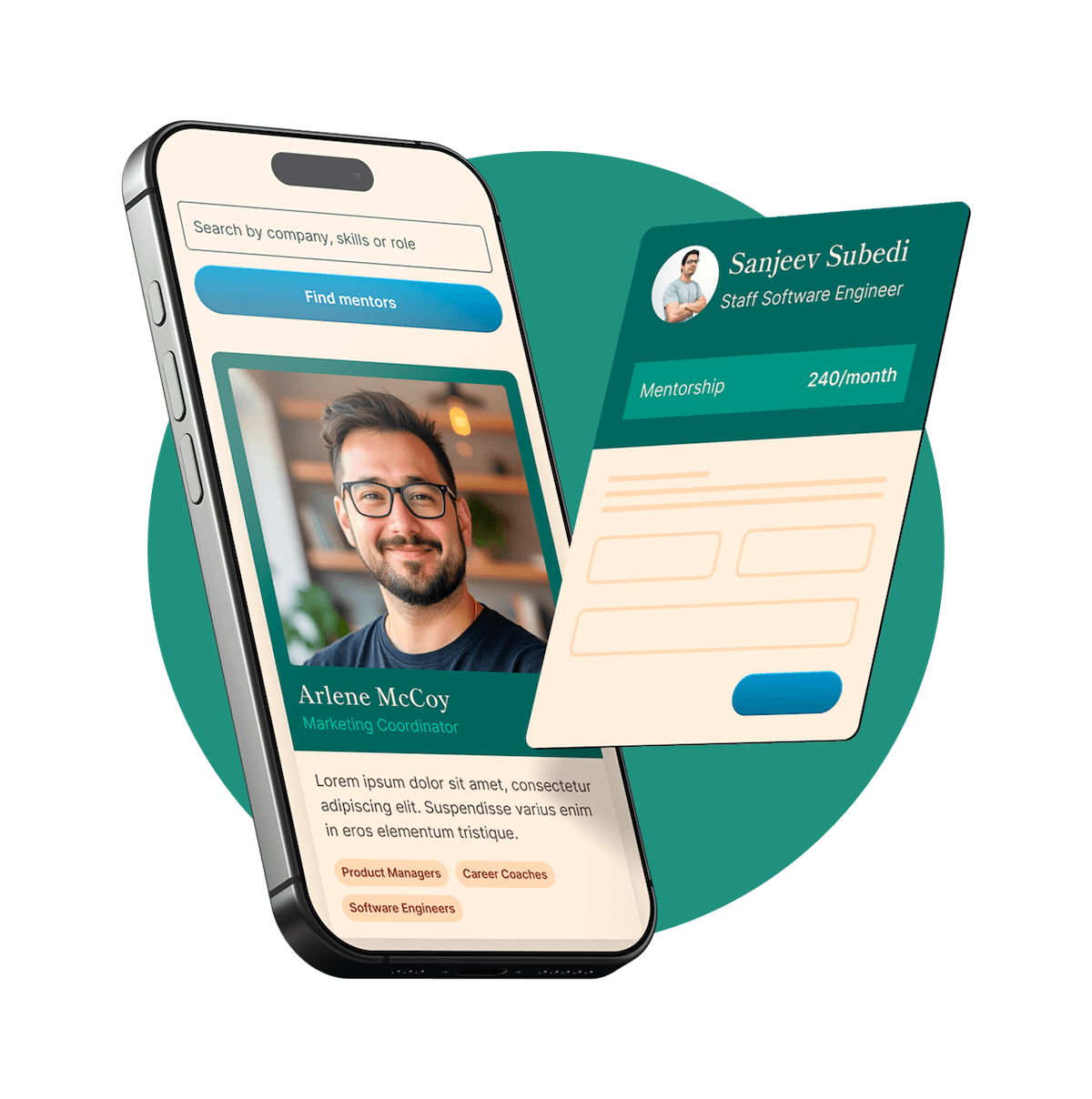

However, its one thing to say "do no harm", "promote wellbeing", or "respect human values" - but what does that look like in practice? How does that translate into your specific situation? Where can you go to talk through a delicate issue in confidence? This is where a tech ethics mentor can help.

Here are few of the ethical areas that are being encountered with AI systems in particular...

- Bias & Discrimination

- Data Privacy and Consent

- Transparency and Explainability

- Auditability and Accountability

Having a tech ethics mentor can provide the support you need to get an objective perspective, learn about resources, share experiences and build your capacity for ethical deliberation in order to manage ethical risks.

But, how exactly, do ethical issues in AI arise?

One way of thinking about this is to break things down into three areas – data, models and people.

The Devil is in the Data

Data is key ingredient for AI systems. Some call data “the new oil” because without a lot of data, AI systems that use machine learning would not be all that functional. Decisions around gathering data have power structures baked into them. For example, if you design a survey, you get to control how many questions are asked, what questions are asked and if there are drop down answers or free text boxes. You will also decide how to reach people to complete your survey and you may choose to target a certain group of people. In essence, you determine the purpose and method of data collection and your choices become encoded in the process.

Historically, we may have more data about some people or things than others because of these decision-making processes. That leads to gaps in available data. For example, we’ve historically collected more medical research data for men than women. This means that we often don’t have adequate medical datasets for women. If that historical data is then used to power an AI system, it may generate biased outcomes. This is known as algorithmic bias.

In our highly digital world, data is being collected all the time. Every online search, every click, every keyboard stroke, we are contributing to a vast web of data collection. There is also meta-data, or data about data, such as geo-location data for your phone. This large volume of constant data collection raises many concerns about privacy and consent, which also contributes to ethical issues in AI.

Mathematical models are not neutral.

Machine learning models can contain bias. Cathy O’Neil, a famous data scientist and author of the book “Weapons of Math Destruction” says that “models are opinions embedded in mathematics.” AI developers make many decisions during the design process, such as deciding what techniques to apply to develop a model, engineering the features that will be contained in a model, and determining the hyper parameters, the over arching guidelines, for training a model. Each decision represents a value judgment on the part of the person making it. For example, using deep neutral networks in order improve technical accuracy may reduce how explainable the model is to people. That trade off is a value judgement which prioritizes accuracy over explainability. There are many decisions like this being made as models are constructed.

People who make a technology shape a technology.

There is a body of work that demonstrates that the people who make a technology shape that technology. We see this in game design. Female characters in a video game are often scantily clad and sexualized, reflecting the fantasies of their mostly young, male creators. Most AI developers are white or Asian men from a certain socio- economic background. Their worldview and values inform the technology. In addition, larger system, such as how funding is allocated, can also set the agenda for the types of technologies that are developed. This was evident in the early days of AI, as much of the funding came from the military during the 1950s and 1960s. Today, large players like Google, Amazon, Facebook and Apple are driving the agenda.

This is not an exhaustive list, just a quick overview of how data, models and people contribute to the ethical issues we see in AI systems.

What specific issues could a tech ethics mentor assist with?

I've been working with my local startup community to provide mentorship to startup founders. Many people come to a session with a particular issue to discuss. Others would like to explore more general education around a topic such as data privacy, data ethics or data governance. Sometimes the question is very broad, such as....

How can we ensure our solution is ethical and isn’t causing harm?

Generally speaking, all of the startup founders I’ve had a chance to connect with are well intentioned people who want to build a solution to make the world better. This itself, however, is a blind spot. There is the need to envision both what might happen if our solution is used maliciously by bad actors and to take appropriate steps to ensure this doesn’t happen. Understanding these harms may require feedback from stakeholders who are not part of the core team, who are not invested in the solution and whose backgrounds are diverse enough to be able to bring a very different perspective to the discussion. In addition to understanding bad actors, startups also need to consider who might be harmed if their technology works exactly as promised.

The field of technology ethics and AI ethics in particular is still rather new. I hope this overview provides some ideas about how ethical concerns might relate to the work you are doing and why you might benefit from a tech ethics mentor.

Photo by Nathan Dumlao on Unsplash