This post was originally published on my newsletter Stratechgist.

Introduction: The Inescapable Reality of Imperfection

The sales team promised: “if we had reporting, this big user would sign a 5 year contract”. I prioritized the reporting functionality, we shipped it, user signed, a success all around. Months later, the user discovered a bug – reports were wrongly aggregated if they straddled more than one calendar year. I didn’t want to prioritize the bugfix because it was a rare use case, and this was the only report of it. “Just tell them to combine multiple annual reports in Excel,” I told their account manager.

She agreed. We both moved on, at the chagrin of the user who signed this 5 year contract.

Software development constantly generates imperfections. Not everything can or should be fixed. No one has unlimited resources, if you’re a team leader you know this firsthand. It’s difficult to prioritize a bug that affects a handful of users over new features that will drive more adoption.

After a few years of prioritizing features, you get a laundry list of bugs that at some point you will have to take care of. As a leader, you’ll have to decide when. If you don't, the alternative is wasted effort on low-impact fixes, critical issues festering, and team morale drained from neverending backlogs.

Every team needs a conscious, strategic approach to managing bugs. You need a framework. Let me tell you about mine: the three Fs. It stands for “Fix, Flag or Forget”. Yes, forget, as in leave it broken.

The Framework: Fix, Flag, Forget

The “three Fs frameworks” categorizes any issue/bug in one of these three buckets:

- Fix It (now or soon). It means I prioritize the bug for resolution in the near term (hotfix, current/next sprint). This implies the value of fixing outweighs the cost.

- Flag It (for future consideration). Bugs that end up in this bucket must be acknowledged and documented. This category gives me the room to defer the decision to fix, while slotting it in a tracker. Tracking bugs requires a system (or at least a tool) for tracking and a cadence to revisit the tracker. It’s critical that the team must not treat this tracker as a dumping ground for all sorts of bugs and issues.

- Forget it (or in other words, consciously decide not to fix): I make an explicit, documented decision that the cost/risk of fixing outweighs the benefit for the foreseeable future. I consider “forgetting” a bug as an active choice, and not neglect.

Let’s dig further into the factors that I look into when making the decision in accordance with the framework.

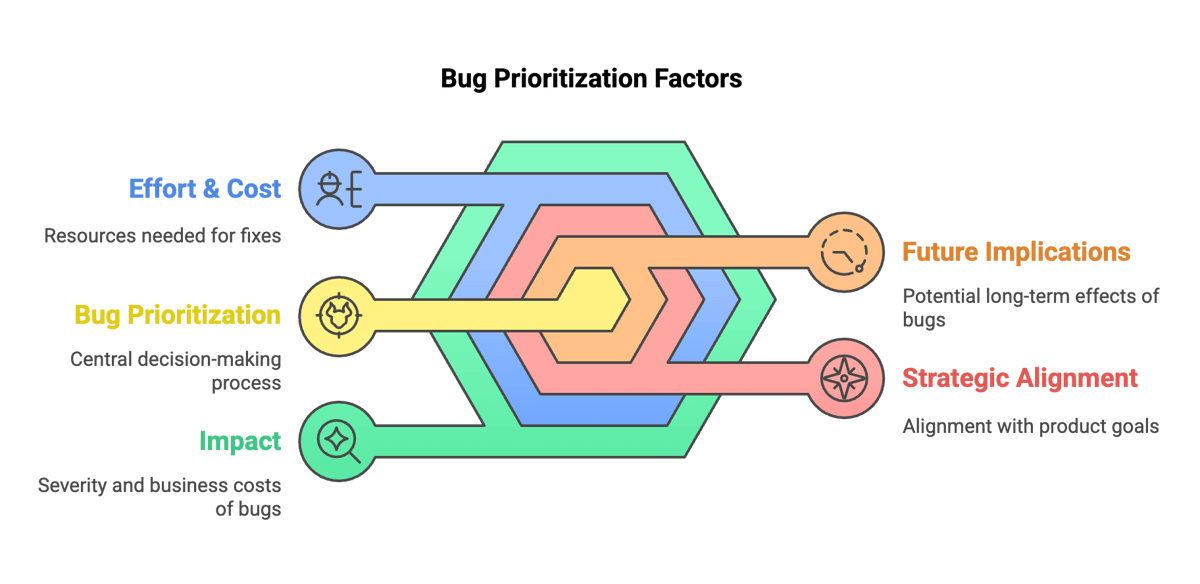

Key Decision Factors

Impact

First things first: impact! Impact is communicated as ‘severity’, a proxy for “How bad is it when it happens?”. The severity of an issue is a wide spectrum. I’ve seen issues ranging from minor user annoyances to system crashes and data loss.

Each bug has an associated business cost. It comes in two flavors: quantifiable and qualitative. In my experience the quantifiable is easier to dig out as it comes as one (or a combination) of the following:

- Lost revenue

- Support costs

- Compliance failure

- Reputational damage

- Productivity loss

The qualitative is the user's pain. My own proxy for it is “how much of the user’s day have we ruined” by them running into the issue. The qualitative cost manifests as frustration, confusion, yelling at support agents, and difficulty with working around the bug itself.

I consider these factors essential when assessing the impact of any bug or regression, as they will allow me to better prioritize the fix.

Effort & Cost

Every fix has an associated effort, which affects the cost. The cost to fix exceptional issues with high severity – e.g. showstoppers – is irrelevant. In all other cases the cost is essential to prioritising a fix.

I find engineering cost estimates most useful, when they are expressed in time (i.e. hours, days) or story points (if the team’s process is Scrum-y). As a leader of a team I take understanding the effort to fix a bug very seriously. We all have limited time on our hands and we have to be careful how we deploy it, so having a good understanding of the effort is essential to prioritize well.

The cost of the fix has correlation with the complexity of the issue at hand. A simple tweak (e.g. copy change) can take minutes to fix, while a structural problem that requires a major refactor can take months. The complexity of a fix is also related to the knowledge required to implement the fix – some fixes are small only to the engineers with specialized knowledge. Picking the person with the right expertise to execute (or oversee) the fix can influence the cost of the bugfix.

Another factor that complicates a fix, and increases its cost, are dependencies. Issues can span multiple systems, services or products. For example, a bug that caused by a timestamp field without timezone support requires a fix in the service backend, a change of the column type in the respective database table, a proto schema change, and bumping the protobuf schema versions on downstream services to adopt the new field, and rolling out all of those services one by one.

To complicate things further, this long chain of changes and dependencies can get blocked. It doesn’t have to be a huge blocker - even a service deployment lock due to an unrelated incident can postpone the bugfix hitting production by hours, days or even weeks.

Finally, I lke to consider the blast radius. Major fixes like refactors are risky. Without excellent test coverage they can introduce new, worse problems, destabilizing the system. I prefer fixes with surgical precision – small, targeted, low-risk changes, easy to test and revert – instead of open-heart surgeries. Precise fixes are low risk.

Strategic Alignment

When it comes to fixing bugs, as engineers we don’t always think about how strategically aligned these fixes are to the current or future goals. More interestingly: does not fixing them block our goals? If a bug is of low impact and it’s not strategically aligned with the product’s direction, then it’s difficult to justify prioritizing it.

Also, the issue might distract the team from higher-priority strategic initiatives. If the team doesn’t have the bandwidth then maybe the bug should not be prioritized now (or ever?).

Sometimes even though there’s no strategic alignment, there might be technical alignment. Some bugs are related to technical debt. In such cases, the bug should be used as additional fuel on the fire to prioritize fixing it, as it’ll be a double whammy – you’re not only fixing a bug, but you’re also paying down debt. I have witnessed bugs that popped up in legacy parts of the system and it’s always neat to use said bugs as an excuse to migrate (part of) the system to newer foundations. As an engineering leader, it’s easier to justify a migration when it’s related to a regression.

Future Implications

Bugs can regress the system over time or over a different dimension (e.g. traffic, load). In the past I’ve launched a new API with a memory leak. In the first days the leak’s memory impact was negligible. But after a couple of days it was completely depleting the server’s memory. We observed that as the traffic grew, also the leakage got bigger, so we not only had to reboot the server every day, but also to sty vigilant for days with elevated traffic. Eventually, we found the leak and fixed it.

The example shows how an issue can creep up and get worse over time or with the increase of use. If we didn’t have good monitoring in place the memory would leak out and the operating system’s OOM killer would reap the server process, leading to downtime.

Issues such as the memory leak also have a delayed cost. The more complex a codebase becomes the more difficult it will be to root cause the leak. That’s why it’s better to work on such issues sooner rather than later.

Worse case scenario would be if such issues become a blocker for new feature development. In other words, neglected issues halting innovation. A nightmare.

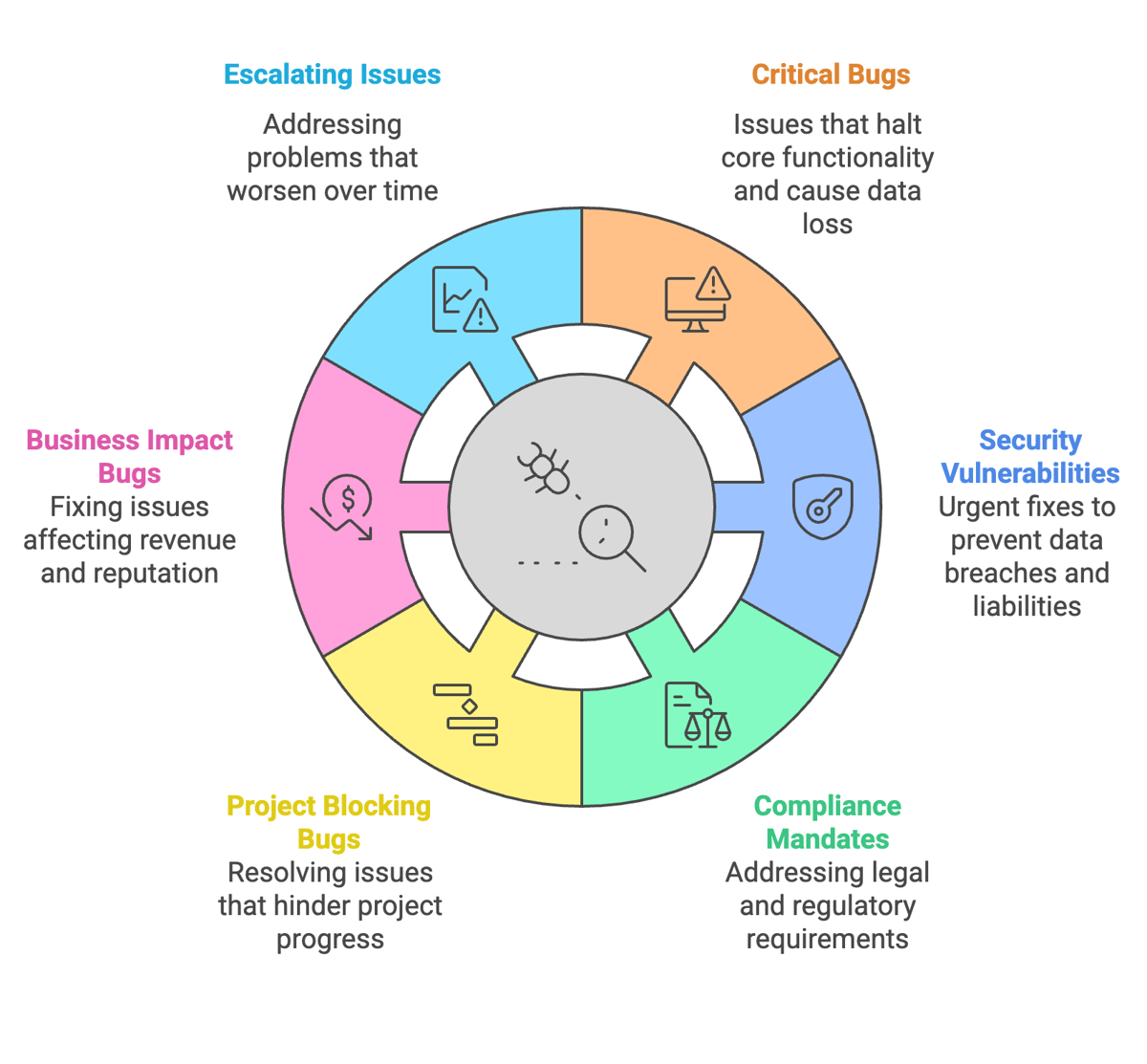

Deep Dive: When to ‘Fix It’

As software engineers we all build the intuition when an issue has to be fixed now v.s. later (or never). As an aspiring engineering leader I’ve been thinking about codifying this: a set of practical criteria when to characterize an issue as a must fix now.

Here’s my loose categorization:

- Critical production bugs. These are issues that “brick” the system. Showstoppers. They block some core functionality, might bring the system down, lead to data loss or data corruption.

- Security vulnerabilities. In my opinion, any vulnerability must be fixed with high urgency as it is good engineering hygiene. I might be biased as I’ve worked in fintech, where vulnerabilities lead to big liabilities. Contingent on your domain, your tolerance to security vulnerabilities might be higher.

- Compliance/legal mandates. Smaller compliance mandates, like amending terms of service, can bring liability to the organization hence it’s good to prioritize them now instead of later. Larger issues, like failing audits or violating regulations result in incidents, which beget a broader and better defined process than just a bug fix.

- Directly blocking high-priority projects. Bugs that block or hinder projects are easy to prioritize, as the bug’s impact is directly felt by the project and the people involved. Often the blocked team itself will gladly fix the bug to unblock themselves.

- Significant, measurable business impact. I like to quickly prioritize bugs that create measurable business impact. Some examples include high support ticket volume, direct revenue loss or severe reputation risk for the company. For example, I have worked on products that have gotten criticism on Hackernews’ front page. You want to jump on fixing that thing right away.

- Rapidly escalating issues. Problems that clearly get worse on their own should be prioritized to the ‘Fix it’ category. An example is the memory leak issue I brought up earlier. This class of problems is especially tricky – if left unchecked they can morph into one of the other categories above.

Any of the above should end up in the ‘Fix it’ category. But just prioritizing them is not enough. Teams must build a muscle to react to this class of bugs; for example:

- Teams have a week-long rotation where an engineer takes one-off work (e.g. user queries, bugs). This engineer can just jump on the issue once it’s been prioritized as ‘Fix it’.

- If no rotation exists, I look for volunteers. Seniority, domain knowledge (where the bug is) and availability are important factors. I don’t want to dump work on someone who already has a full plate. In cases where there is only one subject matter expert, I pair the expert with another engineer to share knowledge.

- The type of issues that provide some grace period (e.g. compliance/legal mandates), can be tackled in dedicated bug-fix sprints in combination with other less-urgent bugs.

The bottom line is that any engineering team must have the mechanisms to tackle important bugs rapidly, with as little interruption as possible. The leader(s) of the team must protect the team during that ordeal and communicate outwards (i.e. stakeholders and leadership) about any side-effects to ongoing projects.

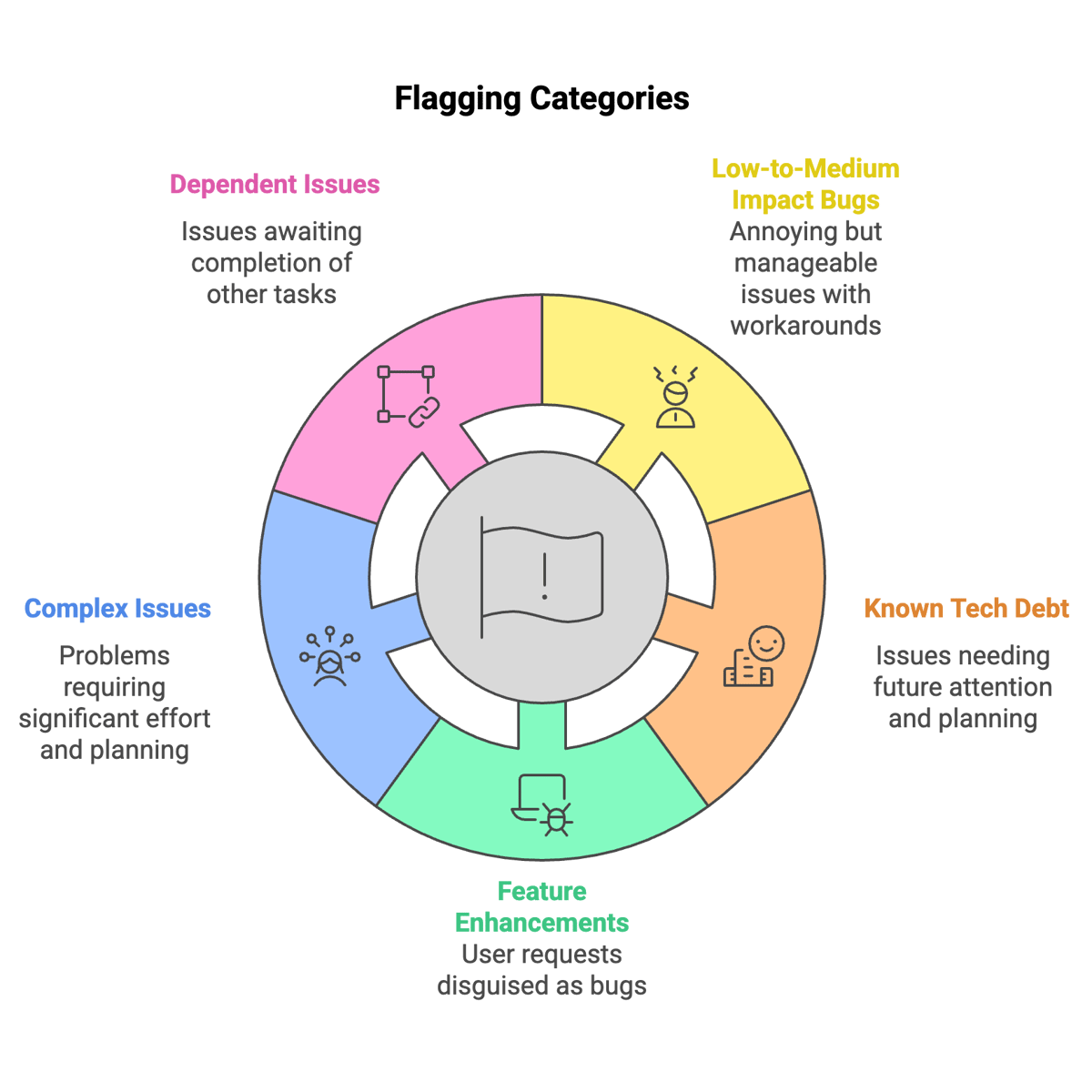

Deep Dive: When (and How) to Flag It

Flagging is great. It allows you to acknowledge a bug yet defer its fixing. But it can be a trap. Flagging can turn the backlog into a graveyard where tickets go to die. To avoid the graveyard situation flagging must be an active bug management process, not a knee jerk reaction.

Here’s my categorization for flagging:

- Low-to-medium impact bugs. These can be annoying to users, but must have workarounds. They must not affect a large % of the user base. If they do affect many users, then they must be cosmetic of nature.

- Known tech debt. Not currently blocking, but identified as needing attention eventually. Requires specific designs and planning phase as the solution is often open-ended.

- Feature enhancements disguised as bugs. Oftentimes users expect a feature to work in a particular way, which they flag as a bug. In fact, the slightly different behavior is essentially a small feature request.

- Issues requiring significant effort/planning. Issues that are too complex to be fixed immediately. These can be issues that span multiple systems or product features, which requires research, design and alignment across multiple teams or functions.

- Issues dependent on future work/refactors. Sometimes it’s just not possible to fix a particular issue without first completing another work item.

As I mentioned before, flagging is tricky. To be effective you need a tight process and to be a bit dogmatic in following it. If you end up skimping on hygiene your backlog will soon overflow with bugs that you don’t even remember why they’re there in the first place.

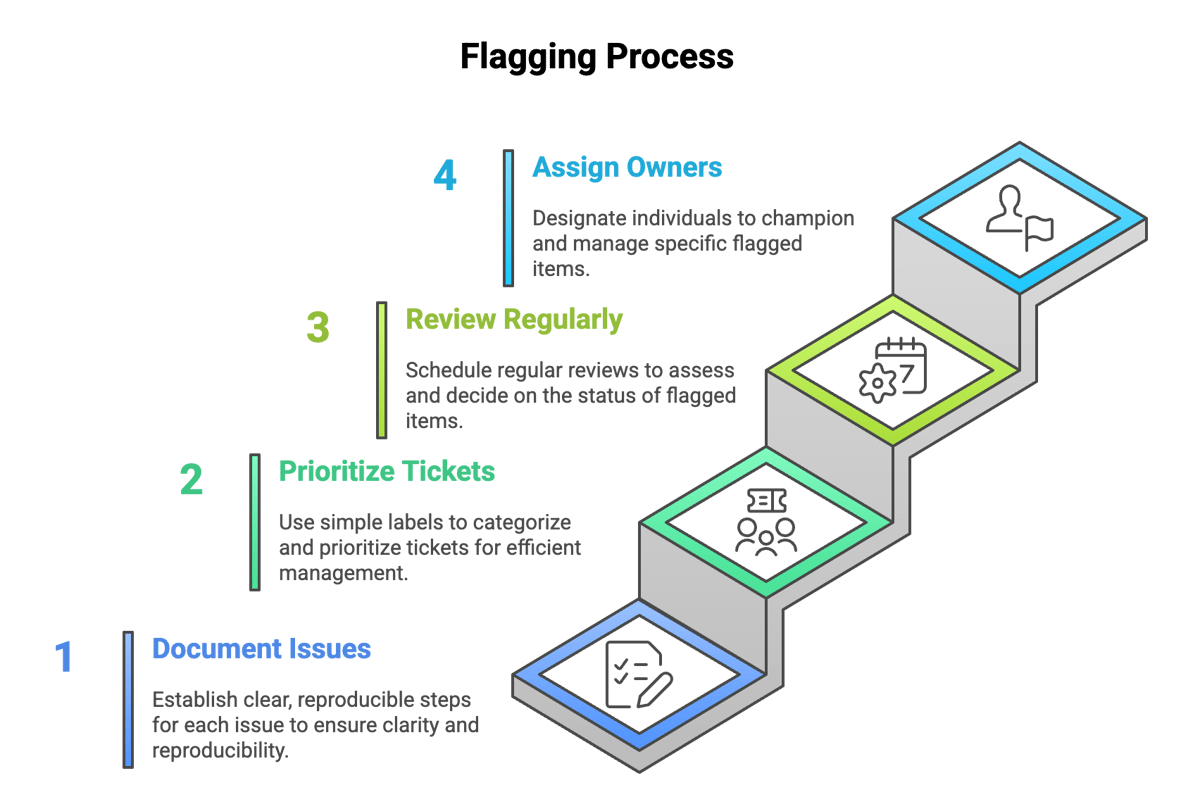

Here’s what effective flagging requires:

- Clearly documented issues. The foundation on which every issue/bug stands on is reproducible steps. If the fixer is not able to reproduce it, the ticket is worthless. The impact assessment must be present (using the factors above!). It’d be nice if the author considered potential solutions, but not required as the solution space is ownership of the team. The estimate (even rough) should be filled in by the engineering team. Links between related tickets should be established, and duplicates (if any) must be closed.

- Meaningful prioritization. Labeling in my opinion is the lowest hanging fruit to ticket segmentation. You need nothing fancy, just fix-it-later as a label is enough. I’ve seen teams use dedicated backlog sections for these tickets (e.g., "Tech Debt Backlog"), which works also OK.

- Regular review cadence. Flagging is not enough, the flagged tickets need to be groomed. I like to set dedicated time (i.e. a reminder on my calendar) to review flagged items. Questions I consider: Has the impact or the cost changed? Does it align with upcoming goals? Then, I force a decision: Fix now, Leave Broken, or Keep Flagged (with justification).

- Set an owner. I like to assign owners or area stewards responsible for championing important flagged items. For example, if I have performance issues lingering on the backlog, I dedicate someone passionate about performance to be the performance champion of the team. They will monitor and escalate the tickets, when relevant.

The bottom line is that any engineering team must have the mechanisms to flag issues with consistency. Allocate specific time for reviewing flagged items. Resist pressure to fix everything immediately if it doesn't meet the "Fix It" criteria.

Deep Dive: When to “Forget it”

Sometimes, the best decision is to do nothing. As a lead, what I always make sure to highlight is that deciding not to fix something is not neglect but a strategic non-action. This requires courage and clear communication, to your users, your stakeholders and your leadership.

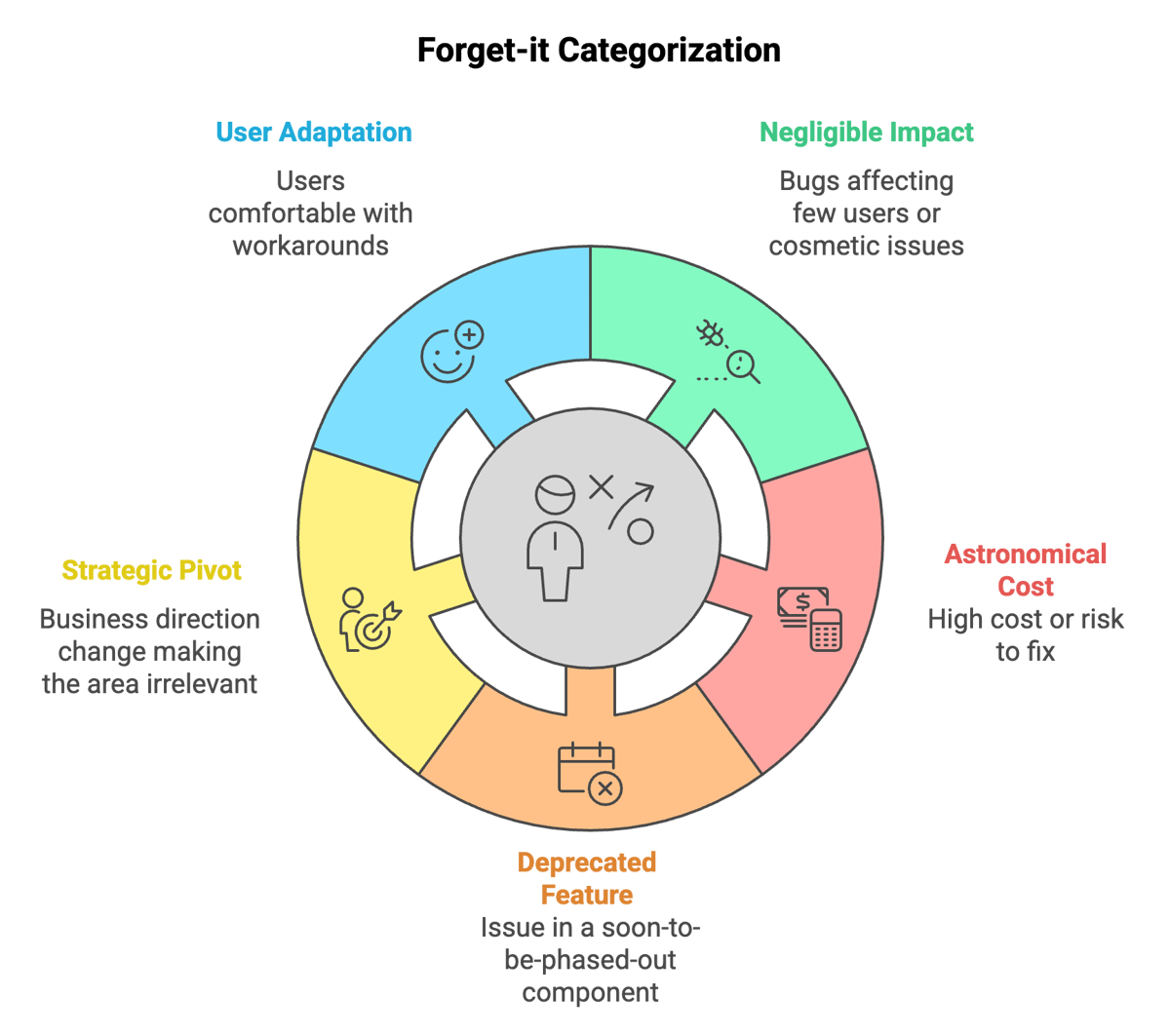

When to leave things broken:

- When the impact is negligible. Extremely rare edge cases, or bugs that affect zero or near-zero active users, or that are purely cosmetic in a non-critical area.

- Astronomical cost or risk to fix. When the fix requires rewriting half the system, or involves significant downtime risk, or uses niche skills no longer available. The ROI is deeply negative.

- Deprecated feature/system. The issue exists in a component that will be phased out soon. Basically, a wasted effort.

- Strategic pivot. The business direction has changed, making the affected area irrelevant.

- User adaptation. Users (or you) have established workarounds they are comfortable with.

As a leader, to decide to leave something in a broken state is not just closing the Jira ticket as “Won’t do”. The decision requires auxiliary artifacts so people (including your future self) can refer back to them whenever needed.

Here’s what I suggest:

- Explicit documentation. Record why the decision was made, the assessed impact, and the date of the decision. This prevents re-litigation unless circumstances change. My team has a decision log (literally an append-only document) where we write down these decisions and put our signature in support of the decision.

- Monitoring, if needed. If you anticipate that there's a risk the issues could get worse over time, it’s best to monitor the frequency and the impact. It’s best to have an automation that would create a ticket or a ping via chat (e.g. Slack) so the team can take action. Consider alerts, but be very conservative with pages.

- Clear communication. As a leader, you have to inform relevant stakeholders or users about the decision and your reasoning. And be ready to defend the team’s decision while being receptive to feedback.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

As with any framework, there are some pitfalls that it’s easy to get into if you do not apply critical thinking to your use of the framework. Some examples:

- The ticket graveyard. Flagging issues without a thorough review process, which results in your team’s backlog turning into ticket backlog that no one ever cleans up.

- Fixing trivial things. Wasting time on low-impact issues due to noise or the temptation for an "easy fix". This is like snacking: you’re taking in calories that don’t really feed you well.

- Ignoring hidden costs. Underestimating the long-term impact of tech debt or annoying bugs on developer velocity and morale.

- Analysis paralysis. Spending more time debating regarding the bug and its fix, than what it would actually take to fix it.

- Poor communication. Making decisions in a vacuum and surprising stakeholders, users or leaders.

If you are looking to grow as an engineer on engineering leader, let’s chat more and schedule your 7 day trial mentorship for free.