The story you’re about to read is based on a real negotiation I advised on some time ago. To protect the companies involved, I’ve changed the names and industry—but the dynamics, decisions, and lessons remain absolutely real.

One of the most delicate moments for a startup is when their first major enterprise customer tries to strong-arm them into giving up something fundamental. A while back I advised a startup—let’s call them CoCreate Health—through one such high-stakes negotiation.

This wasn’t just any deal. It was worth millions of dollars in year-on-year revenue for CoCreate Health. Securing it was vital to their long-term survival and credibility in the market. The negotiation itself was led on the startup side by the two founders and myself as their advisor. One of the founders had a legal background; the other was a tech specialist. We had no internal legal or commercial team—just deep knowledge of the product, clarity of mission, and a strong strategy.

On the other side, the enterprise—NordenCare, a regional public health authority—had brought in heavyweight support. To negotiate the deal, they hired one of the top global law firms and a leading international management consultancy. Names withheld here for confidentiality, but trust me: these were some of the biggest players in the world.

The power imbalance was stark. A tiny healthtech team with a big idea, facing off against some of the most experienced negotiators in the business.

CoCreate had developed a custom analytics platform to help hospital administrators track care quality metrics across dozens of facilities. Everything was on track—until a new group of stakeholders entered the picture.

Some of the tension at this stage was due not to malice, but a fundamental lack of understanding around how tech deals are typically structured and protected. For example, representatives from NordenCare were concerned that if CoCreate went into liquidation, the platform might suddenly become unavailable. Others worried that if the founders exited the company, new owners might not honor the contract. These were valid concerns on the surface—but ones that are easily addressed through standard safeguards such as IP escrow agreements and continuity clauses that survive a change of ownership.

However, one of the key decision-makers within NordenCare went a step further. They questioned whether CoCreate had the capacity to maintain the platform at scale and suggested bringing the entire system in-house. While this may have sounded pragmatic internally, the reality was that NordenCare did not have an internal tech team capable of supporting the platform. They, too, would have had to outsource its maintenance—meaning the risk they feared with CoCreate would simply be transferred, not resolved. In this case, the concern wasn’t just misguided—it was shallow.

Everything was on track—until a new group of stakeholders entered the picture.

These individuals hadn’t been part of the original discussions. But they were now loudly questioning one of the key terms of the deal: that CoCreate retained full ownership of the underlying technology. Despite being standard for SaaS platforms, this suddenly became “unacceptable” to some factions within NordenCare.

Worse still, their tactics weren’t direct. They began ghosting the startup team—canceling meetings, going dark over email, stalling next steps. Classic enterprise pressure. Another tactic adopted was stories—the enterprise began conjuring up narratives that were factually incorrect. Some might say these were “misunderstandings.” We see this a lot in the current geopolitical landscape: if enough people say something is true, it begins to feel like the truth—even when it isn’t. When this starts, it can act like a virus in a negotiation. Swift action is required to remedy this.

And of course, looming over it all was the risk of the startup making a strategic misstep—falling into what we would later categorize as a Lose-Win scenario: CoCreate giving up their IP. That outcome would have compromised their business model and future scalability. There were three highly dangerous variants of this risk: (1) NordenCare forcing a buyout and seizing control of the platform; (2) poor legal representation or miscommunication leading CoCreate to unintentionally surrender IP rights; or (3) CoCreate walking away entirely, losing their first major client and potentially damaging their market credibility. All outcomes would have been deeply damaging, possibly fatal.

For CoCreate, a healthtech startup with limited capital and this being their first large-scale contract, it was a make-or-break moment.

Here’s how we worked through it—and why they emerged stronger, not weaker, in the end.

Step 1: Map the People Before the Problem

First, we built a stakeholder map, the template I used is illustrated further below - note there several various of stakeholder map. I prefer this style and i like to run a workshop with people that have knowledge of the individuals within the target customer. Stakeholder mapping is not just a list of names or departments, but a real assessment of behaviour, power, and positioning:

• Who were the Resources / Operators actually using the platform?

• Who were the Influencers shaping internal opinion?

• Who were the Decision-Makers / Key players controlling the final outcome?

Then we assessed each one’s attitude: were they driving, resisting, silently watching, or passively disengaged?

The analysis revealed a key insight: the real resistance wasn’t coming from users or healthcare professionals. It was coming from legal and risk management staff—none of whom would use the tool, but all of whom could stall the deal.

This was a politics problem, not a product problem. And like all enterprise politics, micro-agendas played a significant role. Some individuals were trying to position themselves for internal influence or career advancement. Others were protecting their turf. We could see clear examples of decisions and delays that had little to do with the actual platform—and everything to do with internal dynamics.

Understanding these micro-agendas was essential. If you take what people say at face value in these situations, you can easily misinterpret their motives. The stakeholder map gave us visibility not only into authority and influence, but also into who had something to gain or lose, regardless of the deal's logic or value.

Take one example: the Head of IT. His micro-agenda centered around demonstrating value for money (VFM). His department had approved and spent a significant sum on the development of a customized version of CoCreate’s technology. But because CoCreate retained ownership of the IP—particularly the new code and platform improvements—there was internal pressure on the Head of IT to justify the spend. What had he actually bought?

Our solution was to build a year-on-year discount into the maintenance contract. On paper, this made it look like the initial CapEx was being “recouped” over time. In practice, that may or may not have been economically true—it’s not hard to inflate perceived savings—but the optics solved the problem. The Head of IT could point to tangible financial value, and his micro-agenda was satisfied.

You can't negotiate with a system—you have to understand the humans behind it. Stakeholder mapping made the invisible visible, and it gave us the foundation for the rest of our strategy.

Step 2: Model the Win-Win (and the Burn)

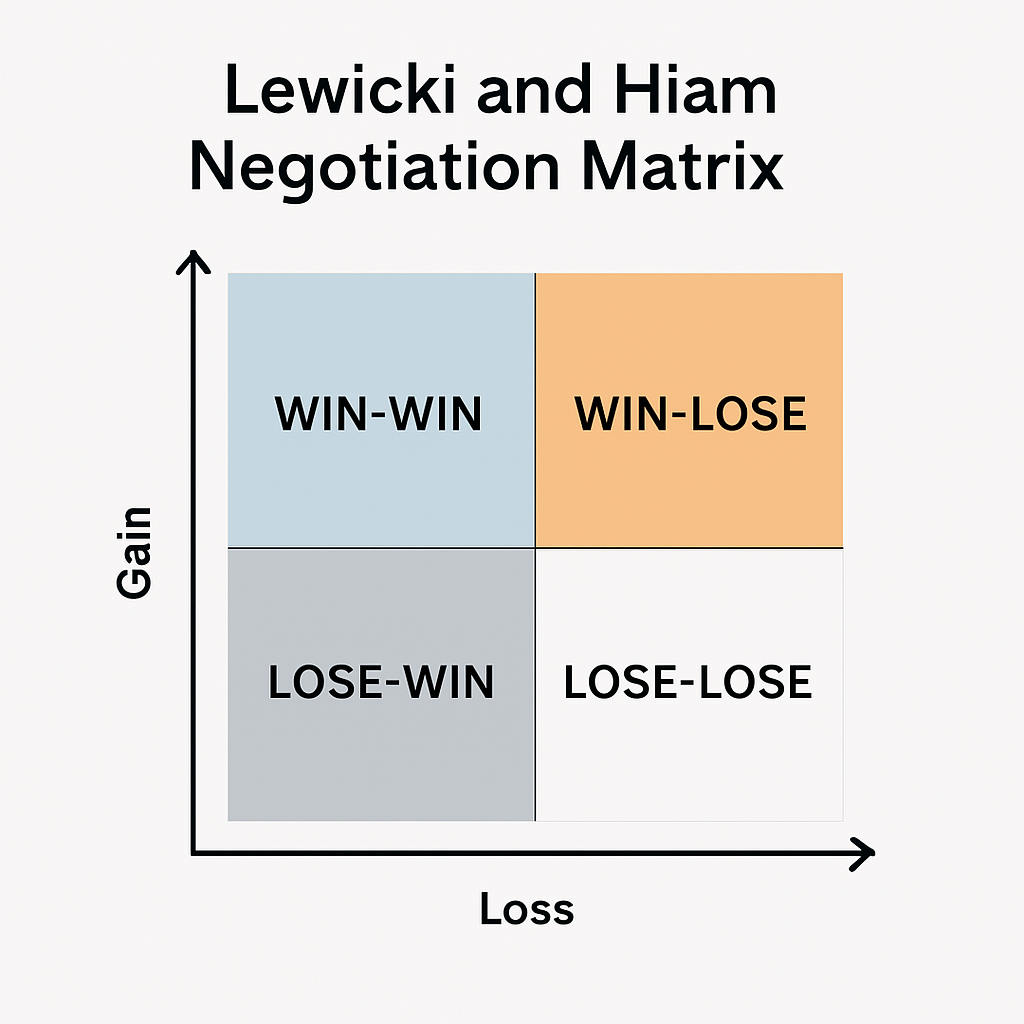

Next, we used Lewicki and Hiam’s negotiation matrix to identify possible outcomes and position our messaging accordingly.

We built out four quadrants:

🔹 Win-Win:

CoCreate retains IP ownership. NordenCare receives full access to the platform, ongoing support, and continuity of service. To provide NordenCare with confidence in the event of unforeseen circumstances—such as CoCreate entering liquidation or being acquired—certain protective rights are granted, and the IP is placed in escrow.

🔹 Win-Lose:

CoCreate retains the IP and NordenCare receives platform access, support, and continuity, but no additional protections. Should CoCreate—a startup—enter liquidation or be acquired, NordenCare would be left exposed with no guaranteed continuity.

🔹 Lose-Win:

CoCreate relinquishes IP rights, compromising its business model and future scalability. Three problematic outcomes include:

1. NordenCare forces a buyout and assumes control of the platform.

2. Poor legal negotiation results in CoCreate unintentionally giving up IP rights.

3. CoCreate is forced to walk away from the deal entirely.

🔹 Lose-Lose:

The deal collapses. NordenCare loses a million-euro digital transformation investment. CoCreate loses its first enterprise customer and a crucial multi-year revenue stream.

We focused our messaging with internal champions on the lose-lose quadrant. No threats—just clear consequences: if this falls apart, everyone loses.

Step 3: Craft Messaging with a Bit of Voss (and a Bit of AI)

Now came the communication challenge.

When you’re in the negotiation battleground, it rarely wraps up in a day. These situations typically stretch over several weeks or even months, and that sustained tension takes a toll. It becomes difficult to switch off from work. You might find yourself losing sleep, overthinking responses, or second-guessing your position. And this mental fatigue can lead to poor decision-making.

That’s why T-CUP—Thinking Correctly Under Pressure—is crucial.

Fortunately, today we have tools that help us stay sharp. One of the most useful? ChatGPT impersonating Chris Voss, the legendary FBI negotiator. Yes, really.

We used ChatGPT in this way to help simulate Voss’s tone and approach. We would draft the messages we wanted to send—raw and unfiltered—and then ask the AI to reframe them using Voss’s tactics: tactical empathy, calibrated questions, mirroring, and emotional neutrality.

This approach not only helped us polish our language but also diffused emotional charge—which is often the invisible toxin in tense negotiations. The output became messages we could send verbally or electronically, and they always came across as clear, professional, and steady.

We’d write what we wanted to say, then prompt AI to transform it into something like:

“It seems like we’re both being pulled by competing pressures. How do you see us moving forward without derailing the work that’s already been done?”

The effect? Clear, human, firm—but not combative. It reset the tone of the negotiation and re-engaged key players.

Step 4: Use the DealLine™

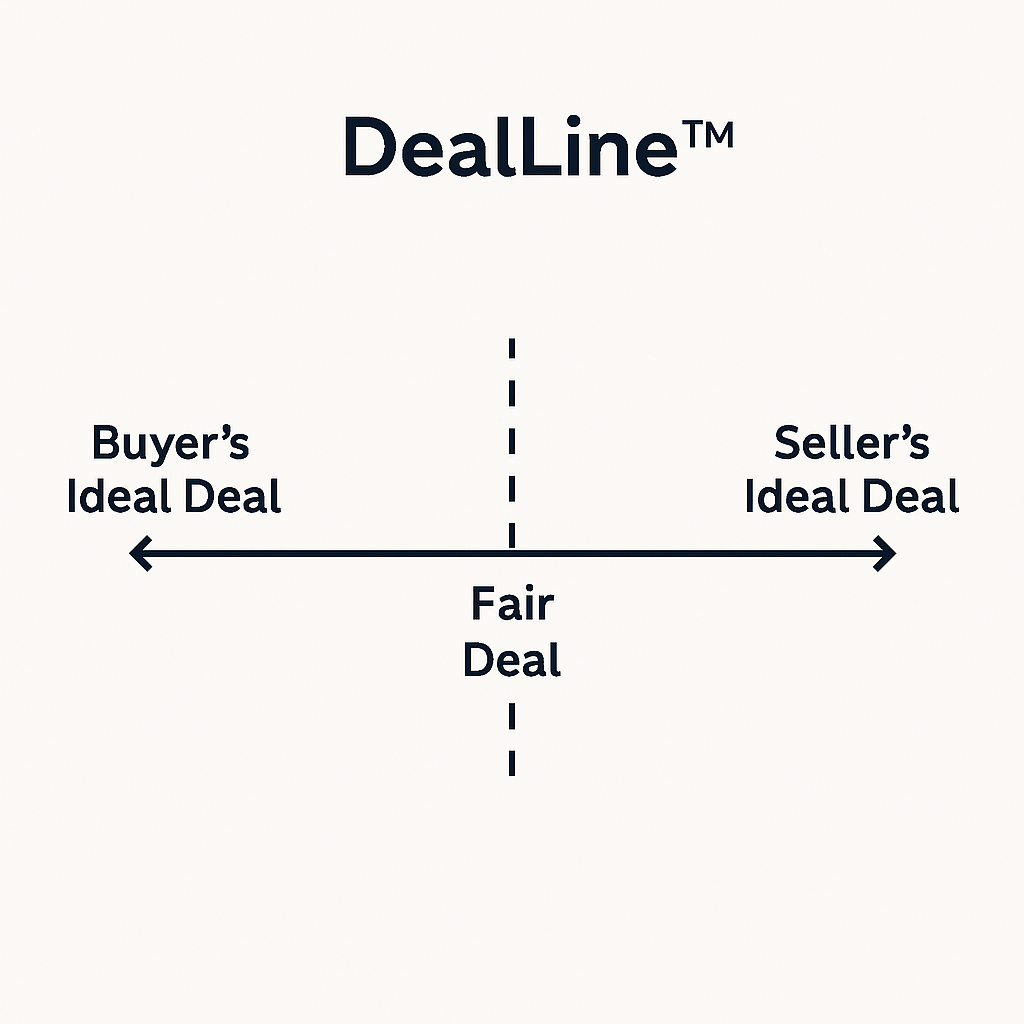

To plan our offer strategy, we used a tool I’ve developed called DealLine™.

It’s simple but powerful:

• Imagine a horizontal line. The buyer’s ideal deal is at one end; the seller’s ideal deal at the other.

• The center is the Fair Deal—where neither party gets everything, but both get enough to move forward.

• Then, we map stakeholders along that line.

Some stakeholders were entrenched at the buyer-extreme end—demanding total control. Others were more moderate, open to compromise. We used DealLine™ to gauge how aggressive or diplomatic our counter-offers should be, depending on who we were speaking with.

Take one example: there was one key decision-maker at NordenCare who sat at the extreme buyer end of the DealLine. Their position was uncompromising—they wanted full IP ownership and planned to remove CoCreate as the ongoing tech provider entirely.

In contrast, several internal influencers had far more grounded concerns. Their focus was on product functionality and achieving their departmental goals. Their micro-agendas had little to do with price or IP—they just wanted a platform that worked and made their jobs easier.

Because the lead decision-maker was so extreme, we made a tactical move: we anchored our first offer at the opposite extreme. We proposed the highest possible price, CoCreate retained full IP, and NordenCare received no additional rights. On the surface, this might seem provocative—but it was intentional.

By setting our stall at the far end, we effectively established the battlefield of the negotiation. From there, we could gradually introduce concessions—small adjustments that gave the appearance of compromise while still protecting CoCreate’s strategic position. Crucially, we retained room to maneuver before even approaching our actual final offer.

This strategic anchoring helped us manage the negotiation tempo, control perceptions, and steadily build toward a workable deal.

The real value of DealLine™ is this: it helps you avoid unforced errors. You don’t offer too much too early to a moderate, and you don’t engage extremists on their terms without a strategy to guide them back toward center.

The Breakthrough: Go Back to the Actual Users

The real breakthrough came not through legal arguments or pricing tweaks, but by reframing the entire negotiation dynamic.

First, we doubled down on something that had been working quietly in the background: the user pilots.

We encouraged CoCreate to engage extensively with the hospital administrators and care managers—the people who would actually use the platform day-to-day. Through these pilot sessions, we gathered a growing body of quantitative and qualitative feedback. Users reported tangible time and cost efficiencies, streamlined workflows, and greater data transparency. But they also surfaced qualitative benefits: less stress, clearer reporting, better team coordination.

This wasn’t just anecdotal support—it was hard proof that the product worked, and that it solved real problems within NordenCare’s operations.

Armed with that evidence, we made a strategic shift.

Rather than continuing to go head-to-head with the legal and risk team—who were entrenched and adversarial—we went around them. We began cultivating buy-in from more senior and horizontally placed decision-makers. This included operational leads, strategy heads, and executive sponsors who cared about outcomes, not ownership.

And it worked.

These internal allies began to apply pressure downward. Momentum shifted. The organization now wanted a deal—not just the users, but the broader leadership. Suddenly, it wasn’t CoCreate facing off against legal and risk—it was the rest of NordenCare.

By the time the final negotiation phase arrived, the legal and risk teams—previously blockers—were almost relieved that someone else was now championing the deal. The pressure to protect the institution no longer fell solely on them. They could take a step back, reposition themselves as validators, and let the forward motion carry things through.

That was the moment everything clicked.

The contract was signed.

The platform was launched.

CoCreate retained full IP ownership.

And NordenCare got exactly what it needed.

Final Outcome

This wasn’t just a contract win—it was a strategic negotiation success in the face of enormous pressure.

CoCreate secured a multi-million-dollar, multi-year deal with a global-scale institution. They retained full IP ownership, established long-term platform continuity, and emerged with a clear value story supported by pilot data, end-user testimonials, and measurable impact.

More than that, the company showed it could go toe-to-toe with elite legal and consulting firms—not by playing the same game, but by playing it smarter.

Through stakeholder mapping, we identified where power really sat and used that to sidestep blockers. By understanding micro-agendas, we defused internal tensions. By using DealLine™, we framed the negotiation battlefield and anchored from a position of strength. And with AI-assisted messaging inspired by Chris Voss, we kept communication steady, strategic, and emotionally neutral throughout.

When internal resistance peaked, we used hard data and organizational momentum to flip the pressure. In the end, the legal and risk teams weren’t adversaries—they were passengers on a train already moving too fast to stop.

CoCreate didn’t just keep the deal—they took control of it.

And in doing so, they gained something even more valuable than a contract:

A repeatable framework for winning complex negotiations against bigger players.

Takeaways for Founders in High-Stakes Deals

Stakeholder mapping is essential. Don’t negotiate with an org chart—map the real power dynamics.

Use Lewicki and Hiam to clarify outcomes. Focus your messaging on what both parties stand to lose.

Don’t wing it—craft your messages. Use Voss-style phrasing and tools like AI to fine-tune your tone.

DealLine™ helps you frame your offer. Calibrate based on where your counterpart sits.

If you’re blocked, go around. Your best allies are often the people who’ll actually use your product.

If you’re a startup facing a big customer negotiation—or worried about protecting your IP in a deal—let’s talk. These situations are hard, but they’re navigable. And with the right approach, you don’t have to choose between your principles and your survival.