With the ongoing Gamestop short-squeeze saga, the practice of market makers paying brokers for order flow has been under public scrutiny. Some claim a potential conflict of interest between Citadel and Robinhood, while others blame HFT funds for market manipulation. [1] [2] Are market makers actually stealing money from the people, or is it actually an enabler for fast, low-cost trading?

Much of this discussion is grounded in a misunderstanding of how market forces work and the roles of each party. Today’s discussion will be an introduction on the mechanics of market making, and if zero-brokerage platforms like Robinhood are really ‘fee-free’.

What is a Market Maker?

Imagine yourself being transported back into the Sixteenth Century — the golden age of merchants and trade. You just returned from your month-long voyage, bringing back exotic spices from Spain. How might you go about selling your precious spices?

You are faced with two obvious problems. You will need to (1) locate individuals that are willing buyers for your spices, and (2) determine a fair price to sell your spices at. What are the chances that someone will want your spices at this very moment? — practically none. You want the money right this instance, given that you are exhausted from being at sea.

This is where a market maker comes in — a middleman that provides liquidity by facilitating as both a willing buyer and seller. In order to sell your spices, you simply need to locate a market maker who will quote you a price they are willing to buy your spices for. The market maker then seeks out a willing buyer of spices, taking on the risk of having to hold onto the inventory.

Can You Make Me a Market?

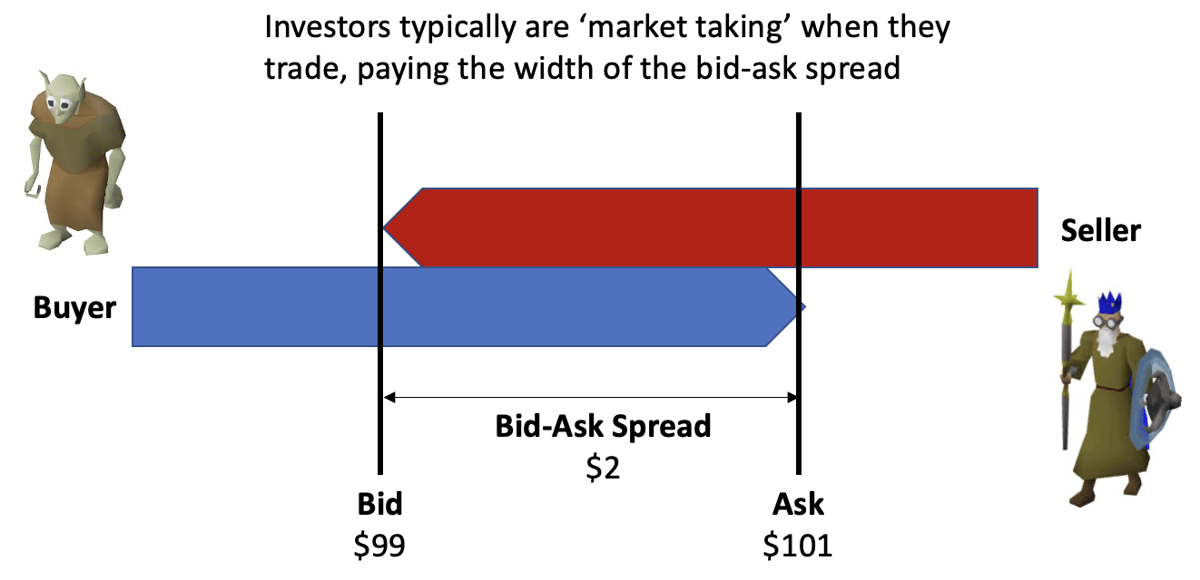

Today when you wish to purchase Gamestop stock, most investors are ‘market taking’ or ‘crossing the spread’ and are paying the width of the bid-ask spread. When you log on to Schwab to place a trade on GME and see that its bid-ask spread is $99-$101, here is what you are really doing.

For starters, a ‘bid’ is a price that someone is willing to buy something for, and an ‘ask’ is a price that someone is willing to sell something at. If you want to buy a stock, you will need to pay $101 and conversely, if you wanted to sell a stock, you will receive $99.

Given the dynamics of supply and demand, the ‘fair value’ of a stock at that point in time will be somewhere between $99 and $101. For simplicity, let us take the fair value as the halfway point. So whenever you use a ‘$0 brokerage platform’, you are in reality still implicitly paying a fee of $1 via the spread (although you are still saving on brokerage fees).

Market makers are the middleman that set the bid-ask spread, and play a function in always providing liquidity even at times of market crashes. Ideally they want to pair up buyers with sellers so that they hold no inventory or take on zero risk. However this is not always possible, and so they are compensated through the spread for taking on this risk.

There is a common misconception that market makers are ‘front-running’ the market. This is the act of seeing non-public information of a large order, and then buying some stock in order to then move the market so that you can sell the stock back at a higher price. Not only is this completely false, it is also highly illegal. Believe me, I have sat through far too many compliance talks, and certainly did not want to risk prison time while I was a market maker. [3]

This dynamic results in consumers being better off. Not only are they able to access liquidity instantaneously, competition between different market makers ensure that the bid-ask spread is as tight as possible. [4]

So How Do Market Makers Actually Make Money?

As illustrated above, market makers make money based on its ability to match buyers with sellers so that they are able to profit from the spread.

Let us suppose that you are Jane Street and that someone bought 150 shares of Apple from you (your position is now -150). Now 5 minutes later, someone else sold 120 shares of Apple to you (your position is now +120). These shares cancel out against each other, leaving you with a net position being short 30 shares.

If the spread of Apple shares was 10 cents, then the market maker had just profited $12 through these two trades. As long as the market maker can approximately achieve two-way flow, where buyers can be matched to sellers, then profit will be made.

Before you decide to do this, it is important to note that there is still a net position of short 30 shares. If the price of Apple stock moves adversely against you, or upwards in this case, then you will be losing money on your trades. Oftentimes market makers are exposed to selection bias, resulting in them often being on the wrong side of the trade.

Hence making a market is an artform to ensure that you are being adequately compensated for taking on risk, while being simultaneously competitive enough. If the spread is too tight, you will take all order flow from your competitors but take on a loss. If the spread is too wide, none of your orders will be filled. In general, the wider the spread means the more volatile the stock.

A market maker’s ideal situation is to manage risk appropriately, and then to process as much volume as possible. This is where ‘high frequency trading’ (or HFT) comes in, where computers are used to transact stock orders extremely quickly. Market makers like IMC with extremely low-latency systems are able to place trades before their competition — it is a game of speed.

A top-tier market maker transacts over a trillion dollars in order flow every year, while taking on roughly a 50bps spread — amounting to $5 billion dollars in revenue. [5] It is worth pointing out that given how tight and competitive the spreads are, it is pretty common for market makers to not be making money after accounting for their risk. This is an extremely competitive industry, with plenty of market makers losing money — in fact, I was a part of the process in purchasing the book of another market maker that had closed down.

Of course, there are other ways market makers can make money such as by trading volatility, or by taking on a directional view. However, market making remains the central focus of their operations, with other extracurricular trading strategies being secondary.

The Role of an Exchange

Okay so we have talked about how market makers make money, and how it is great for market takers wishing to place a trade. So what is the purpose of an exchange then?

An exchange is simply a marketplace that facilitates trading activity. These include the New York Stock Exchange, the Australian Stock Exchange, or even cryptocurrency exchanges such as Bitmex. There are a lot of different variations in business models, but generally there exists a ‘maker-taker’ model.

If we have a look at Bitmex fees, we can see that there is a ‘maker-fee’ of -0.025% and ‘taker-fee’ of 0.075% for Bitcoin. This means that market makers are being paid a rebate to provide liquidity on the platform, whereas ordinary traders pay an additional 7.5bps to the exchange when crossing the spread.

The maker-taker model is there to incentivise market makers to provide liquidity on their platforms, which would thereby attract more customers. In the early days of Bitcoin, it was quite difficult to transact it due to the lack of liquidity present on any reliable exchanges. The exchange then stands to make a profit from the maker-taker spread — everything is about spreads!

Are Market Makers Actually Good?

Due to the highly competitive nature of market making, customers ultimately benefit from many firms fighting for order flow. This is the backbone for many exchanges and retail brokers, allowing for extremely low fee trading.

The prevalence of market makers helps establish liquidity in new markets such as the emerging Asian markets, cryptocurrencies, and even houses with the rise of Zillow. They also ensure that the markets are resilient in times of stress, with Jane Street being instrumental in keeping the bond ETFs market liquid during the 2020 crash. [6]

Lastly, market makers face an extreme amount of regulation according to SEC Rule 605 (formerly 11Ac1–5). According to regulatory data, retail traders benefited $3.6 billion in 2020 as a result of lower trading costs that have been partially brought on by market makers.

If you liked the article, you can support me by following me on Twitter or visiting my mentoring profile.

Powered by Froala Editor