Master your next Swift interview with our comprehensive collection of questions and expert-crafted answers. Get prepared with real scenarios that top companies ask.

Prepare for your Swift interview with proven strategies, practice questions, and personalized feedback from industry experts who've been in your shoes.

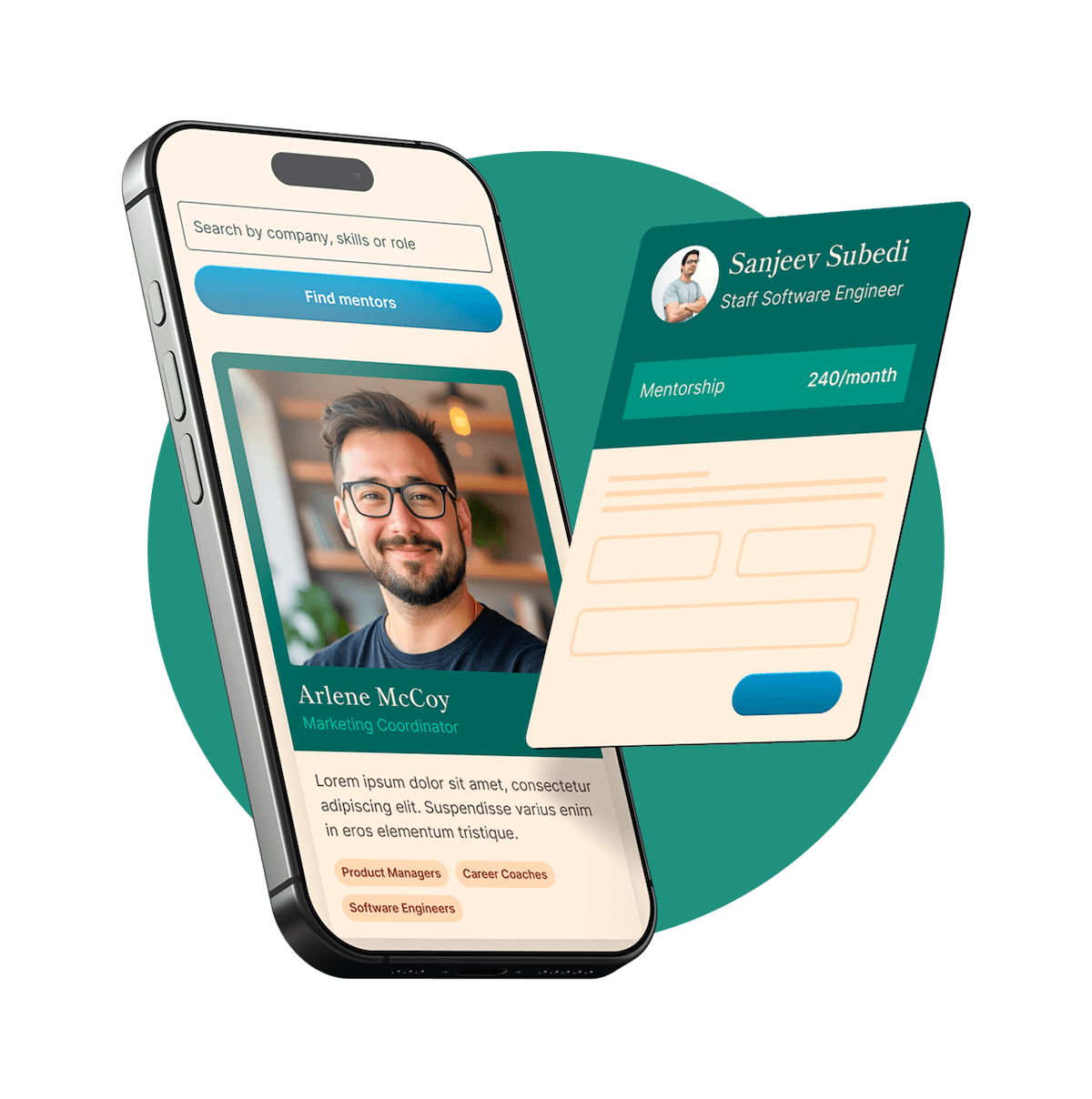

Thousands of mentors available

Flexible program structures

Free trial

Personal chats

1-on-1 calls

97% satisfaction rate

Choose your preferred way to study these interview questions

In Swift, variables and constants are defined in a simple and straightforward manner. For variables, you use the "var" keyword followed by the name of the variable, and then assign a value to it. For example:

Swift

var name = "John"

In this example, name is a variable, and it has been assigned the string "John". You can change the value of name at any time later in your code because it's a variable.

On the other hand, constants are defined using the "let" keyword, and once a value is assigned, it cannot be changed. Here's an example:

Swift

let pi = 3.14159265359

In this case, pi is a constant, and it has been assigned the value 3.14159265359. You cannot change the value of pi later in your code – if you try to, the compiler will throw an error. This gives you a way to clearly express that a value is meant to stay the same throughout your program, which can help prevent bugs and make your intents clearer when other people read your code.

In Swift, let and var are both used to declare variables, but they do so with one essential difference: let is used to declare constants, while var is used to declare variables.

When you declare a constant with let, you are saying that its value cannot be changed once it is set. So, if you try to change it, the compiler will throw an error. This can be useful when you have a value that you know should not change, like the number of days in a week:

Swift

let daysInAWeek = 7

On the other hand, when you declare a variable with var, you are signaling that the value can be changed on the fly. Here's an example:

Swift

var currentTemperature = 20

currentTemperature = 25

In this code, currentTemperature is a variable. We initially set it to 20, but then change its value to 25 — this code is perfectly valid, because currentTemperature is a variable and not a constant.

In Swift, error handling is done through a mechanism of throwing, catching and propagating errors. This is unlike some other languages that use exceptions.

Here's the basic process. First, you define an error type which typically would be an enumeration that conforms to the Error protocol:

Swift

enum PrinterError: Error {

case outOfPaper

case noToner

case onFire

}

To throw an error from a function, you mark the function with the throws keyword:

Swift

func sendToPrinter(_ file: String) throws -> String {

if file == "No Toner" {

throw PrinterError.noToner

}

return "Job sent"

}

Then, when calling a function that can throw an error, you use a do-catch statement to catch and handle the error:

Swift

do {

let printerResponse = try sendToPrinter("No Toner")

print(printerResponse)

} catch PrinterError.onFire {

print("I'll just put this over here, with the rest of the fire.")

} catch let printerError as PrinterError {

print("Printer Error: \(printerError).")

} catch {

print(error)

}

In this case, if sendToPrinter throws an error, the appropriate catch clause is used to handle the error. If no errors are thrown, the code continues on as normal. It's a robust approach that helps to ensure any potential errors are properly dealt with.

Try your first call for free with every mentor you're meeting. Cancel anytime, no questions asked.

In Swift, an optional represents a variable that can hold either a value or no value at all. It's a safe way to say "there might be a value, there might not". The idea of optional helps to avoid runtime errors in the system by making the absence of a value perfectly clear.

For instance, consider a situation where you have a dictionary of people and their ages. But not everybody in the dictionary has an age associated with their name. If you were to try and get the age of a person who has no age in the dictionary, you would get a nil value.

Here's how you might use an optional to deal with this:

Swift

var agesDictionary = ["James": 25, "Sarah": 30]

let age = agesDictionary["John"]

In this situation, "age" is an optional integer, because there might not be an age for "John" in the dictionary. To safely unwrap this optional, you could use an if-let statement or a guard-let statement to provide a default value in case "age" is nil.

Swift and Objective-C are both languages used for iOS app development, but they offer different approaches and syntax. Objective-C has been around for about three decades and is based on the C language, so it carries more historical baggage and complexity. Swift, on the other hand, is a relatively new language developed by Apple, designed to be more user-friendly and safe. Its syntax is much cleaner and easier to read than Objective-C.

It offers features such as type inference, which means the developers don't have to explicitly define the data type, making coding faster and less prone to errors. Swift also doesn't have pointers, unlike Objective-C, making it safer as the risk of accidentally manipulating data in wrong ways is reduced. In terms of performance, Swift is usually faster than Objective-C, as it was built with modern hardware and software in mind.

Lastly, memory management in Swift is done with Automatic Reference Counting (ARC) across both methods and functions which is more efficient, while in Objective-C ARC is only available in object-oriented code. Despite these differences, Swift and Objective-C can be used together in the same project, so developers can enjoy the best of both worlds.

A tuple in Swift is a type that groups multiple values into a single compound value. The values within a tuple can be of any type and do not have to be of the same type as each other. Here's an example:

Swift

let httpStatus = (404, "Not Found")

In this case, httpStatus is a tuple that contains an Int and a String. You can access the individual elements in a tuple using a dot followed by the index:

Swift

print(httpStatus.0) // Prints "404"

print(httpStatus.1) // Prints "Not Found"

Compared to arrays and dictionaries, tuples are a way to temporarily group related values together. Arrays and dictionaries are collection types that hold multiple values of the same type and provide a more flexible way to manipulate a collection (such as adding or removing elements), with values accessed by index or key.

Tuples, on the other hand, are usually used to contain a fixed number of related elements. They are especially useful when you need to return multiple values from a function. Unlike arrays or dictionaries, you can't add or remove elements from a tuple after it's defined.

Ensuring thread-safety in Swift involves managing the access to shared resources among different threads. One common way is to use Grand Central Dispatch (GCD), specifically dispatch queues, for synchronization.

Dispatch queues are thread-safe which means any code put inside the queue will run in a sequential and predictable manner. If you have a piece of code that writes or modifies a shared resource, you would want to put that code in a serial queue to ensure that only one thread could access the resource at a time.

Here's a simple example:

swift

let queue = DispatchQueue(label: "com.example.mySerialQueue")

queue.sync {

// Your thread-safe code here

}

Another mechanism is using locks, such as NSLock or os_unfair_lock. A lock prevents other code from executing until the lock is unlocked. However, using locks requires more care as improper use could lead to deadlocks or priority inversion.

Swift also provides the @Atomic property wrapper (from Swift 5.1) which ensures that property's setter and getter are mutually exclusive, providing a level of thread-safety.

Although these mechanisms provide a way to achieve thread-safety, it's crucial to design your program to minimize the need for shared access to resources which leads to better performance and less potential for bugs.

Swift handles memory management with a system called Automatic Reference Counting, or ARC. Whenever you create an instance of a class, ARC allocates a chunk of memory to store information about that instance. This information includes the type of instance, its properties, and the methods associated with the instance.

With ARC, Swift keeps track of the number of active references to each class instance. When the number of references to an instance drops to zero, meaning no part of your code is using the instance anymore, ARC frees up the memory used by that instance so it's available for other purposes.

However, to prevent memory leaks due to strong reference cycles, Swift also provides weak and unowned references. If two class instances hold a reference to each other and they are released, they cannot get deallocated, causing memory leak. Weak and unowned references help resolve these strong reference cycles, giving Swift a robust and efficient system for memory management.

Get personalized mentor recommendations based on your goals and experience level

Start matchingError handling in Swift is primarily done with the throw, try, catch, and finally keywords.

First, you define an Error type that can represent different error scenarios. These are often implemented as enumerations. For instance:

swift

enum PrinterError: Error {

case outOfPaper

case noToner

case malfunction

}

Next, a function that can throw an error includes throws in its declaration:

swift

func processJob(on printer: Printer) throws -> String {

if printer.isMalfunctioning {

throw PrinterError.malfunction

}

// rest of the processing code

}

Then, when calling a function that throws errors, you use try and handle the errors using a do-catch statement:

swift

do {

try processJob(on: myPrinter)

} catch PrinterError.outOfPaper {

print("Out of paper. Please refill.")

} catch PrinterError.noToner {

print("No toner. Please refill.")

} catch PrinterError.malfunction {

print("Printer malfunctioning. Please contact tech support.")

} catch {

print("An unknown error occurred: \(error).")

}

In the above example, if an error is thrown, execution jumps into the catch block that matches the error and processes it. If an error isn't thrown, the do block completes without issues. The catch blocks are checked in sequence, so more specific errors should be placed before more general ones.

Finally, you could use try? or try! when calling a throwing function, if you want to handle errors in a simpler or more forceful way respectively. These alternatives either convert the error to an optional or cause the program to crash if an error occurs.

Swift is a multi-paradigm language, meaning it supports multiple programming styles, including functional programming. Here are a few of the ways you can use functional programming paradigms in Swift:

Immutability: To minimize side effects and unexpected behaviors, use more constants (with let keyword) and fewer variables (with var keyword).

Higher order functions: Swift's standard library includes a plethora of higher-order functions like map, filter, reduce, forEach, which take in functions as arguments, or return a function, allowing your code to be concise and readable.

Swift's functions are first-class citizens: You can assign a function to a variable or constant, pass a function into another function as a parameter, or have a function return another function.

Use more value types (structs and enums) and fewer reference types (classes). Because value types are copied upon assignment, it's harder to introduce bugs by accidentally sharing and mutating state.

Swift supports pattern matching which we mostly use in switch statements.

Optional chaining is another functional programming style Swift provides. It allows to chain multiple calls together and will automatically stop at the first nil encountered.

Swift supports creation of generic types and functions which promote code reusability.

Remember, just because you can use functional programming paradigms in Swift doesn't mean you always should. Good Swift code often mixes object-oriented, imperative, and functional styles, using each where it most makes sense.

Delegation is a design pattern in Swift where one object hands off, or delegates, some of its responsibilities to another object. It's a way of designing your code so that one object will perform some work and then notify another object when the work is done. It's used to customize or manipulate the behavior of a function or a class with input or behavior from another class.

For example, a common usage of the delegation pattern is when you have a UITableView in your app. Your view controller can act as the delegate for the table view, meaning the table view can hand off some decision making to the view controller. The UITableViewDelegate protocol includes methods like didSelectRowAtIndexPath, which is called when you tap on a row in the table.

Here's a simple example:

```swift class MyViewController: UIViewController, UITableViewDelegate { @IBOutlet weak var tableView: UITableView!

override func viewDidLoad() {

super.viewDidLoad()

tableView.delegate = self

}

func tableView(_ tableView: UITableView, didSelectRowAt indexPath: IndexPath) {

print("Row \(indexPath.row) was selected")

}

}

``

In the example,MyViewControlleradopts theUITableViewDelegateprotocol, setting itself as the delegate oftableView. When a row is selected,tableViewdelegates the handling of that action toMyViewController`, which then prints out a log message.

The delegation pattern is used extensively in UIKit, and you’ll find that delegation is a fundamental concept to grasp when building iOS apps. It fosters a well-organized and clearly-structured code base, by allowing objects to interact with each other over well-defined protocols.

In Swift, type aliasing is used to provide a new name for an existing data type. It's created using the typealias keyword. Once you define a type alias, you can use the alias anywhere you would use the original type.

Here's an example:

```swift typealias WholeNumber = Int typealias Message = String

let count: WholeNumber = 10 let greeting: Message = "Hello" ```

In this example, we declared WholeNumber as a new name for Int, and Message as a new name for String. From then on, you can declare variables of type WholeNumber or Message, and they behave just as Int or String.

Type aliases don't create new types. They're simply "nicknames" for the existing types. Their primary use is to make code more clear, especially if a certain data type has a specific meaning in your context. They can also simplify complex types like tuples and closure signatures, or be used to import platform-specific types in a cross-platform way.

In Swift, both classes and structures are used to define custom data types, and they can have properties and methods. But there are a few key differences.

Structures are value types, which means when a struct is assigned to a new variable or constant, or it's passed to a function, it's actually copied. Any changes to the copy do not affect the original instance. This can be useful for data that needs to be encapsulated, entities that represent a specific value, or any case where you want to ensure that the data won't be changed unexpectedly.

On the other hand, classes are reference types. When you assign a class instance to a new variable or constant, or pass it to a function, it is the reference that is copied, not the data itself, meaning that changes to one reference will affect all other references to the same instance. This is useful when you want multiple parts of your code to interact with the same data.

Lastly, unlike structs, classes can inherit from other classes, enabling more complex behaviors. Moreover, Swift also allows checking and casting of types in case of classes, and classes can be deinitialized to free up resources whereas structs cannot.

A guard statement in Swift allows for early exit from a scope (like a function or a loop) if a certain condition is not met. It can make your code cleaner and more readable by reducing the amount of nested if statements.

The syntax is guard followed by the condition. If the condition is not met, it executes the code in the else block, which should exit the current scope using return, break, or an equivalent way.

Here's an example of how a guard statement might be used:

Swift

func greetPerson(name: String?) {

guard let name = name else {

print("No name provided")

return

}

print("Hello, \(name)!")

}

In this example, the greetPerson function tries to print a greeting including the provided name. However, the name is an optional. The guard lets us exit the function early if name is nil, preventing the rest of the function from running with an invalid value. If the name is not nil, it's unwrapped and assigned back to name variable, which can be used normally in the rest of the function.

Closures in Swift are self-contained blocks of functionality that can be passed around and used in your code. They are similar to functions in that they can take in parameters and return values, but are also more flexible and lighter-weight.

Closures can capture and store references to any constants and variables from the context in which they are defined. This is known as closing over those variables or constants, hence the name "closures".

Here's an example of a simple closure:

Swift

let addNumbers = { (num1: Int, num2: Int) -> Int in

return num1 + num2

}

let result = addNumbers(3, 5) // result is 8

In this example, addNumbers is a closure that takes in two integers and returns the result of adding them together. Later in the code, you can call this closure similar to a function and the returned value is stored in result. This makes closures extremely handy when you want to keep a piece of code in a variable and execute it at your convenience. Notable uses of closures in Swift include array methods like map, filter, reduce; and also as completion handlers for asynchronous API calls.

In Swift, you can declare a variable's data type explicitly or Swift can infer it implicitly based on the value you assign to that variable.

Explicitly declaring the type is when you specifically write out what type your variable is. You do this by placing a colon and the type after the variable's name at the point of declaration. Here's an example:

Swift

var name: String = "John"

In this case, we explicitly tell Swift that name is of type String.

On the other hand, an implicit declaration lets Swift infer the type based on the initial value. So it's enough to just assign the value and Swift will infer the type. Here's an example:

Swift

var age = 25

In this example, because we assigned an integer number to age, Swift implicitly sets the type of age to Int. We didn't have to write age: Int, Swift inferred it on its own based on the assigned value.

In general, implicit typing helps keep code cleaner and more readable, but explicit typing can provide clarity in complex cases or when the variable is declared without an initial value.

In Swift, didSet and willSet are property observers. They're special methods that are called whenever a property's value is set, allowing you to perform additional actions before or after the value change.

willSet is called just before the value is stored. Within the willSet method, you can access the new property value using the newValue keyword. Here's an example:

Swift

var count: Int = 0 {

willSet(newCount) {

print("About to set count to \(newCount)")

}

}

In this case, the message "About to set count to (new value)" will be printed each time count is about to be set.

On the other hand, didSet is called immediately after the new value is stored. You can access the old property value using the oldValue keyword:

Swift

var count: Int = 0 {

didSet {

print("Count changed from \(oldValue) to \(count)")

}

}

So whenever count is set, this code will print out something like "Count changed from 0 to 1".

You could use willSet and didSet to validate or adjust the value of properties, or to keep track of changes and take actions when a property's value is changed.

Generics in Swift are a way to write flexible, reusable code that can work with any type, while still preserving type safety. The concept is similar to using a placeholder, instead of an actual type. Once you go to use this generic item, you then define the placeholder's actual type.

For instance, consider an array. An array can hold integers, strings, or any other type. Behind the scenes, Swift implements this using generics.

Here's a basic generic function example:

swift

func swapValues<T>(_ a: inout T, _ b: inout T) {

let temp = a

a = b

b = temp

}

In this example, T is a placeholder type. This means a and b can be of any type, but they must be of the same type as each other. This function swaps their values no matter if they are Int, String, or any other type.

So the power of generics lies in their ability to provide flexibility while maintaining type checking, allowing us to write more reusable and cleaner code.

In Swift, variables can hold either a strong or a weak reference to an object.

A strong reference is the default type, meaning that as long as there is a strong reference to an object, that object will not get deallocated. For example:

swift

var myClassInstance = MyClass()

In this case, myClassInstance holds a strong reference to the instance of MyClass, keeping it in memory.

On the other hand, a weak reference doesn't stop Swift's memory management system, known as ARC (Automatic Reference Counting), from deallocating the object it references if there are no more strong references to it. This can be useful to prevent retain cycles, which occur when two objects hold a strong reference to each other and can't be deallocated. A weak reference must be optional and is automatically set to nil when its object is deallocated. Here's how you might use it:

swift

class MyClass {

weak var reference: OtherClass?

}

In this example, reference is a weak reference to an instance of OtherClass. If all strong references to the OtherClass instance are removed, then reference will automatically become nil, allowing the OtherClass instance to be deallocated.

Ultimately, you would generally use strong references unless you're looking to prevent a retain cycle, in which case you would use a weak reference.

In Swift, a closure is said to escape a function when the closure is passed as an argument to the function, but is called after the function returns. We use the @escaping keyword while defining the function to indicate that the closure may outlive the function call itself. This typically happens in asynchronous tasks where the function returns immediately, but the closure is called at a later point in time.

Here's an example of an escaping closure in a function that takes a closure as an argument and calls it asynchronously:

Swift

func asyncTask(completion: @escaping () -> Void) {

DispatchQueue.main.async {

completion()

}

}

In contrast, a non-escaping closure is a closure that is passed as an argument to a function and is called within the function's body, before the function returns. By default, closures are non-escaping. Usually, the closures are executed and then they go out of scope once the function returns.

Here's an example of a non-escaping closure:

Swift

func calculate(values: [Int], using calculation: ([Int]) -> Int) -> Int {

return calculation(values)

}

In the above example, the calculation closure is called and completes within the scope of calculate function, hence it's a non-escaping closure.

These classifications are primarily used to help optimize memory management for your Swift code and to ensure your code works as expected.

Dealing with JSON data in Swift typically involves decoding JSON into native Swift objects using the Codable protocol, which combines the Encodable and Decodable protocols.

Suppose you have a JSON object representing a person with a name and age. First, you define a struct that matches the format of the JSON and make it conform to Codable:

swift

struct Person: Codable {

let name: String

let age: Int

}

To convert the JSON data to a Person object, use JSONDecoder:

```swift let jsonData = """ { "name": "John Doe", "age": 35 } """.data(using: .utf8)!

do { let person = try JSONDecoder().decode(Person.self, from: jsonData) print(person.name) // Outputs: John Doe } catch { print("Error decoding JSON: (error)") } ``` In this case, if the JSON data matches the structure of the Person struct, it is decoded into an instance of Person that you can use in your Swift code.

Similarly, if you want to convert a Person object to a JSON object, you can use JSONEncoder.finishEncoding.

Remember that handling JSON in Swift involves a certain reliance on getting well-formed JSON. If the JSON structure doesn't match your data types, there can be errors during the decoding process. So, proper error handling is also an essential part of dealing with JSON in Swift.

Networking in Swift is generally performed through URLSession, a built-in API that manages data tasks such as making HTTP requests.

Common tasks include creating a URL object from a string, creating a URLSessionDataTask, then calling the "resume" method on the task to start it. Completion handlers can be used to handle the response data and potential errors.

Here is a basic example of a GET request:

```Swift let url = URL(string: "https://api.myserver.com/data")!

let task = URLSession.shared.dataTask(with: url) { (data, response, error) in if let error = error { print("Error: (error)") } else if let data = data { // Handle data } }

task.resume() ```

In this example, an HTTP GET request is made to the specified URL. The return data is captured in the "data" constant. If there's an error, it is captured and we can print or handle it accordingly.

You will often use a JSON decoder to convert the returned data into native Swift objects if your API returns JSON data. Note that networking tasks can take some time, URLSession performs them in the background and calls the completion handler on the main thread when done.

In Swift, computed properties are those that do not actually store a value. Instead, they provide a getter and an optional setter to retrieve and set other properties and values indirectly.

Here's a basic example of a computed property in Swift:

```swift struct Square { var sideLength: Double

var area: Double {

get {

return sideLength * sideLength

}

set {

sideLength = sqrt(newValue)

}

}

}

var mySquare = Square(sideLength: 4) print(mySquare.area) // Outputs: 16

mySquare.area = 9 print(mySquare.sideLength) // Outputs: 3 ```

In this code, the Square struct has a sideLength stored property and an area computed property. When you ask for the area of the square, Swift will multiply the sideLength by itself to return it. And when you set the area, Swift sets the sideLength to be the square root of the new area.

Computed properties can make it easier to manage and manipulate data in your structs and classes, keeping the data consistent and the interface controlled. They can be used with classes, structures, and enumerations.

Type inference is a feature of Swift where you don't explicitly have to declare the data type of a variable or constant. The Swift compiler is intelligent enough to infer the type of the variable or constant from its initial value.

For example, if you write:

swift

let greeting = "Hello, World!"

Swift uses type inference to recognize that greeting should be a String, because the initial value is a String.

Type inference also works with complex expressions, not just initial values. Swift can infer the result type of an expression based on the types of its operands:

swift

let sum = 21 + 21 // Swift infers that 'sum' is of type 'Int'

Type inference provides a balance between flexibility and type safety. It reduces verbosity in your code (you don't have to declare types all the time), but you still get the benefits of strong type checking by the compiler. This minimizes the likelihood of type errors, making your code more robust.

Encapsulation in Swift is achieved through the use of classes, structs, and enums, along with access control modifiers. These let you control the visibility of properties and methods, making sure only the bare minimum of data needed is exposed.

Swift includes five access levels: open, public, internal, fileprivate, and private. By default, all entities have internal access level.

Classes, structs, and enums each provide a way to group related data and functions together. For example:

```Swift class Employee { private var salary: Int

init(salary: Int) {

self.salary = salary

}

func giveRaise(amount: Int) {

salary += amount

}

} ```

In this class, salary is a private property. It cannot be accessed directly from outside the Employee class. Instead, there's a giveRaise function to modify it. This ensures the salary property isn't accidentally changed to an invalid state - it can only be modified through the giveRaise method. This is the encapsulation principle: hiding the internal states and implementation of an object and exposing only what is necessary.

Access control in Swift is a system that restricts access to certain parts of your code from other parts of code. It's used to hide the implementation details and to control how other parts of your code can interact with the data structures and functions it encapsulates. The main benefit is that it helps prevent data from being used in an incorrect way.

Swift provides five access control levels:

Open and public: Enables an entity to be accessed from any source file in any module, but open allows the entity to be overridden or subclassed from different modules, while public does not.

Internal: Allows an entity to be accessed within its own module but not in any source file from outside the module. This is the default level of access.

Fileprivate: Restricts the use of an entity to its own defining source file.

Private: Restricts the use of an entity to the enclosing declaration, and to extensions of that declaration that are in the same file.

These levels provide a very flexible way to restrict and allow access to different parts of your code based on your needs. Remember effective use of access control can help keep your code safer and cleaner.

A protocol in Swift defines a blueprint of methods, properties, and other requirements that suit a particular task or piece of functionality. It's essentially a contract that says, "If a type wants to conform to me, it needs to have these functions or properties."

Protocols can be adopted by classes, structs, and enums to provide implementations of the requirements. Once a type declares that it conforms to a particular protocol, it must implement the methods and properties that the protocol defines. This allows for some abstraction and flexibility in your code.

For example, suppose we have a protocol called Flyable, which requires any adopting type to have a fly() method:

swift

protocol Flyable {

func fly()

}

And then we have a Bird class that adopts and conforms to this Flyable protocol:

swift

class Bird: Flyable {

func fly() {

print("The bird is now flying")

}

}

In this case, Bird adopts the Flyable protocol and provides a concrete implementation for the fly() method. It's not limited to classes - structs and enums could also conform to the Flyable protocol. This system brings a lot of flexibility and is key in allowing Swift to be a Protocol-Oriented Programming (POP) language.

An enumeration, or enum, in Swift is a data type that has a discrete set of named values, known as cases. Enums are used to model a type that can only take one of a certain set of values - like the days of the week, directions (north, south, east, west), the status of a task (complete, in progress, not started), etc.

Here's a simple example:

Swift

enum Direction {

case north

case south

case east

case west

}

In this case, Direction is an enum that represents four cardinal directions. You could then use this enum like this:

Swift

var travelDirection: Direction = .east

In addition to basic enums, Swift provides associated values, which allows extra information to be stored along with the case value, and raw values, where each case can be assigned a pre-populated value of a certain type.

You can also add computed properties and methods to enums, making them very powerful and flexible. They are a central part of Swift and are extensively used in Swift's standard library.

Grand Central Dispatch (GCD) is a technology developed by Apple that allows you to manage the execution of tasks concurrently or asynchronously. It makes it easier to design and write multi-threaded code and allows the system to balance loads for better, more efficient use of system resources.

At the center of GCD are "dispatch queues", which are essentially pipelines where tasks are executed in the order you've added them. By default, these tasks are executed sequentially so you'd add tasks to the queue and they execute one after the other.

Three types of dispatch queues are provided by GCD:

Main Queue: This queue is serial and executes task on the application’s main thread. It's used to perform work on your app's user interface.

Global Queues: These concurrent queues share pool of system-managed threads and execute multiple tasks simultaneously.

Custom Queues: These are queues that you create yourself, which can be serial (like the Main queue) or concurrent.

For example, if you would like to perform a task in the background, you could use GCD to dispatch the task into a global background queue:

swift

DispatchQueue.global(qos: .background).async {

// code to execute in the background

}

And if you want to update the UI after the background task, you can dispatch a closure onto the main queue:

swift

DispatchQueue.main.async {

// code to update UI

}

These abilities make GCD a powerful tool for improving app performance and responsiveness.

Lazy variables in Swift are variables that are not calculated or loaded until the first time they're accessed. They're declared by using the lazy keyword before their declaration.

This can be useful when the initial value for a variable is computationally expensive, and thus should only be done if and when the variable is actually going to be used.

Here's an example:

```swift class DataLoader { init() { print("DataLoader initialized") // Imagine this loading process takes a long time or memory... }

var data = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5] // Some bulky data...

}

class ViewController { lazy var dataLoader = DataLoader()

init() {

print("ViewController initialized")

}

}

let vc = ViewController() // Prints: ViewController initialized print(vc.dataLoader.data) // Prints: DataLoader initialized, then: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5] ```

In this example, DataLoader is not initialized when we create our ViewController. Only when we access dataLoader.data does the DataLoader instance get created and its data loaded.

This can be very beneficial for improving initial load performance for your objects, but be careful, as the first access to the lazy property is always a blocking call. If the lazy property were to perform a network call, for example, you'd block the main thread on first access. As with anything, use this tool judiciously!

Control flow in Swift is primarily managed by looping constructs (for-in, while, repeat-while), conditionals (if, guard, switch), and control transfer statements (continue, break, return).

Loops: for-in loops over items in a sequence such as an array, set, or range of numbers. while performs a set of statements until a condition becomes false. repeat-while is similar to while, but it performs its statements at least once, checking the boolean condition after each pass.

Conditionals: if runs a block of code based on the truth of a condition. guard is similar to if but it's used when a condition must be met in order for the code to continue execution, it's mainly used for early exit. switch considers a value and matches it against several possible matching patterns, and then executes an appropriate block of code based on the first pattern that matches successfully.

Control transfer Statements: continue ends the current pass of a loop and jumps immediately to the start of the next pass. break ends execution of the immediate enclosing control statement. return ends execution of the current function and returns a result if the function is not defined with a void return type.

These constructs let you program a variety of non-linear code paths, making them vital for any substantial Swift codebase.

Sure. Swift has a number of benefits for iOS development:

Safety: Swift is designed with a strong focus on type safety and ensuring your code doesn't crash due to null pointer exceptions.

Speed: Swift is also extremely fast, often outperforming C++ for certain algorithms.

Modern Features: Swift integrates a number of modern language features, such as generics, optionals, and closures, which make it powerful, expressive, and easy to use.

Interoperability: You can use Swift and Objective-C in the same project, making it easy to adopt Swift progressively in an existing project.

Active Development: Swift is under active development by Apple, which regularly rolls out updates and enhancements.

However, Swift also has some drawbacks:

Changing Language: Because Swift is still evolving, sometimes updates can introduce breaking changes, which can require developers to update their existing code to the new syntax.

Smaller Community: Although growing rapidly, Swift's community is still smaller than languages like Objective-C or Java, which can mean less third party libraries and resources.

Limited use outside Apple ecosystem: While this is changing with efforts like Swift on server, use of Swift is largely limited to Apple ecosystem which can limit its use for some projects.

Despite the drawbacks, Swift remains a very strong choice for iOS development due to its performance, safety, and modern, clean syntax.

Extensions in Swift allow you to add new functionality to an existing class, structure, enumeration, or protocol. This includes the ability to extend types for which you do not have access to the original source code, commonly known as "retroactive modeling". You’d use extensions to break out functionality related to a class, or just to keep your code organised.

Suppose you want to extend Swift's built-in Int type to add a method that checks if it's even or not, you can do it like this:

```swift extension Int { func isEven() -> Bool { return self % 2 == 0 } }

let number = 5 print(number.isEven()) // Prints "false" ```

In this example, we've added a new function isEven to Int that wasn’t there before. Now, every Int has that method available.

It's important to note that extensions can add new functionality, but they can't override existing functionality. Extensions can also add new computed properties, but they can't add stored properties or property observers. If you need to add behavior that changes the existing nature of an object, you'll need to create a subclass instead.

Unit tests in Swift can be written by leveraging the XCTest framework provided by Apple. Here's a simple step-by-step guide:

Create a new Unit Test Case Class. In Xcode, you can do this by clicking File > New > File > Unit Test Case Class.

The new file will contain a subclass of XCTestCase with setUp(), tearDown(), and example test methods.

```swift import XCTest @testable import YourProjectName // Import the module you want to test

class YourProjectNameTests: XCTestCase {

override func setUp() {

super.setUp()

// Put setup code here. This method is called before the invocation of each test method in the class.

}

override func tearDown() {

// Put teardown code here. This method is called after the invocation of each test method in the class.

super.tearDown()

}

func testExample() {

// This is an example of a functional test case.

// Use XCTAssert and related functions to verify your tests produce the correct results.

XCTAssert(true)

}

} ```

XCTAssertEqual, XCTAssertTrue, etc.Here's an example of a real test method:

```swift func testPersonInitialization() { let name = "John Doe" let email = "[email protected]" let person = Person(name: name, email: email)

// affirm the person was correctly initialized

XCTAssertNotNil(person)

XCTAssertEqual(person.name, name)

XCTAssertEqual(person.email, email)

} ```

This test case creates a Person and verifies its properties were correctly set.

Writing unit tests like these can help you catch and prevent bugs in your code, ensure your code behaves as expected, and make it easier to refactor or add new features in the future.

Inheritance is a fundamental characteristic of object-oriented programming, and Swift allows class types (not struct or enum) to inherit properties, methods, and other characteristics from another class, known as its superclass. The class that inherits these characteristics is called a subclass.

To declare a subclass in Swift, you place the name of the superclass after the subclass’s name, separated by a colon:

```swift class Vehicle { var speed = 0 func honk() { print("Honk! Honk!") } }

class Car: Vehicle { var numberOfWheels = 4 }

let myCar = Car() myCar.honk() // Outputs: "Honk! Honk!" print(myCar.numberOfWheels) // Outputs: 4 ```

In this example, Car is a subclass of Vehicle, so it automatically gets the speed property and the honk method from Vehicle. Car can also add its own properties and methods (like numberOfWheels) or override the inherited ones.

Overriding is done by using the override keyword in the subclass. To call a method, property, or subscript from the superclass from an overridden method, you use the super prefix.

It's worth noting that Swift has a single inheritance model, meaning that each class can have at most one superclass. This prevents a multitude of problems that can come from multiple inheritance.

Model-View-Controller (MVC) is a design pattern that separates objects into one of three categories: Models for data, Views for user interface, and Controllers to bridge Models and Views. Here's a rudimentary example of each part:

Model:

Models represent the data and logic of your application. They don't know anything about the user interface. An example could be a Person struct with name, email fields and a greet() function.

```swift struct Person { let name: String let email: String

func greet() -> String {

return "Hello, I'm \(name), my email is \(email)"

}

} ```

View: Views represents the user interface. They display data to the user and capture user interaction, typically built with UIKit/SwiftUI.

Controller: Controllers act as a bridge between models and views. They control the data flow between the model and the view, and vice versa.

```swift class PersonViewController: UIViewController { @IBOutlet weak var nameLabel: UILabel! @IBOutlet weak var emailLabel: UILabel!

var person: Person!

override func viewDidLoad() {

super.viewDidLoad()

nameLabel.text = person.name

emailLabel.text = person.email

}

}

``

Here,PersonViewControlleris a controller. It uses thePersonmodel to populate the view'snameLabelandemailLabel` UILabels.

In an MVC architecture, data flows from model to controller, then from controller to view, maintaining a separation of concerns. User actions captured in the views are transmitted back to the model via the controller. This leads to a decoupled and more maintainable code architecture.

Always remember to keep the controllers lean and manage dependencies well to avoid "Massive View Controller" problem, where too much responsibility or too many things are jammed into the view controller.

Automatic Reference Counting, or ARC, is a system that Swift uses to track and manage memory usage for your application. Every time you create a new instance of a class, ARC allocates a chunk of memory to store information about that instance. When the instance is no longer needed, ARC frees up that memory so it can be used for other purposes.

ARC works by maintaining a count of current references to each class instance. If an instance has no existing references, ARC knows that it can safely deallocate that memory as it's no longer in use.

For instance, when you assign a class instance to a variable or constant, or pass it to a function, ARC increments the instance's reference count. When the variable or constant goes out of scope, or is reassigned to another object, ARC decrements the reference count of the instance.

```swift var myVar: MyClass?

func someFunction() {

let myInstance = MyClass() // ARC allocates memory for myInstance

myVar = myInstance // Increment reference count for myInstance, made by the assignment

} // myInstance goes out of scope and ARC decrements its reference count

someFunction()

myVar = nil // Decrement reference count of myInstance to 0, freeing up the memory occupied by myInstance

```

One important aspect to consider about ARC is retain cycles, where two class instances hold strong references to each other and cannot be deallocated by ARC. This is usually handled using weak or unowned references.

Overall, ARC almost entirely automates memory management in Swift, preventing common mistakes like double frees, use after free, and memory leaks, while also making the language easier to use.

In Swift (and programming in general), synchronous and asynchronous tasks refer to different ways of handling operations that might take some time to complete, often involving I/O such as network requests or disk operations.

A synchronous operation blocks the current thread of execution until it is finished. This means that if a synchronous operation is running on the main thread (which is also where all UI update occurs), your application will freeze, or appear frozen, until that operation completes.

swift

print("Start")

let data = try? Data(contentsOf: someURL) // This is a synchronous network request

print("End")

With the above code, "End" gets printed only after the data from someURL is downloaded completely.

Contrasting that, an asynchronous operation returns immediately, allowing the thread it was called on to continue executing. It usually takes a closure (often referred to as a 'callback') that gets called when the operation is finished.

swift

print("Start")

URLSession.shared.dataTask(with: someURL) { (data, response, error) in

print("End") // This is called when the data is finished downloading

}.resume()

In this code, "End" probably gets printed after "Start" because the dataTask(with:completionHandler:) method returns immediately, before the data is fully downloaded.

Asynchronous operations are fundamental to developing responsive applications. Without them, networking requests or heavy computations would make UI unresponsive and create a poor user experience. However, managing asynchronous code can be more challenging because it involves handling state across different points in time, hence it's one of the common topics to understand in Swift (and iOS) development.

A singleton is a design pattern that restricts a class to a single instance, so that this single instance can be accessed from everywhere in the code. This is useful for things like managing a shared resource, such as a network session or a database.

Here's an example of creating a singleton in Swift:

```swift class MySingleton { static let shared = MySingleton()

private init() {

// This prevents others from using the default '()' initializer for this class.

}

func doSomething() {

print("Doing something...")

}

} ```

To use this singleton, you refer to MySingleton.shared:

swift

MySingleton.shared.doSomething() // Prints: "Doing something..."

In this example, shared is a static constant assigned a new instance of MySingleton. Because init() is private, no other code can instantiate MySingleton. All accesses to the singleton go through the shared variable. This design ensures that there's exactly one instance of MySingleton throughout your program.

While singletons can be useful, they should be used sparingly. Because they're globally accessible, they can make code harder to understand and test, and create couplings between disparate parts of a codebase.

Swift uses Automatic Reference Counting (ARC) to manage memory. Each time a class instance is assigned to a variable or constant, or passed to a function, its reference count increases by one. ARC deallocates the instance by decrementing the reference count each time that instance is no longer strongly referenced.

However, this can sometimes lead to retain cycles, especially when there are strong references between instances of classes (like when declaring parent and child objects). To deal with this, Swift provides weak and unowned references.

Weak references: When declaring a variable as weak, the reference to the object does not increase the reference count. It's used mostly when there can be a cyclic chain of references.

Unowned references: Similar to weak, unowned does not increase the reference count. But it’s used when we know during the lifetime of that object, the unowned reference will always have a value.

ARC in Swift only applies to instances of classes. Structs and enumerations are value types, not reference types, and are not stored and passed by reference.

While ARC handles most of the memory management in Swift, developers still need to understand and anticipate possible "retain cycles" to prevent memory leaks and enhance performance.

Knowing the questions is just the start. Work with experienced professionals who can help you perfect your answers, improve your presentation, and boost your confidence.

Comprehensive support to help you succeed at every stage of your interview journey

We've already delivered 1-on-1 mentorship to thousands of students, professionals, managers and executives. Even better, they've left an average rating of 4.9 out of 5 for our mentors.

Find Swift Interview Coaches